The fascinating thing about volunteering down at Oswego’s Little White School Museum is you just never know what interesting bit of local history will walk through the door to brighten your day. And if your family has been lurking around these parts as long as mine has, sometimes those bits have a family connection, too.

A few weeks ago, one of those bits arrived when the son of a childhood friend of mine and his wife poked their heads in my office and said they had something that might interest me. And it did, both historically and personally.

The hinge was missing from the lid on the small, oval-shaped copper-colored tinned box—quite obviously a snuffbox—he showed me, but otherwise it was in pretty good condition. Smiling, he suggested I look closely at what was scratched in the metal box lid, and after turning it to catch the light I could make out “Tom Kelly.”

He’d found it while cleaning out his great-grandparents’ attic, did a little internet research on Tom Kelly, which pointed him to my interest in Tom and his twin brother, John. How the snuffbox got to the attic of Jim and Elizabeth “Bess” McMicken is a complete mystery.

Back in July of 2012, about five months after I started this blog, I published a post about twin boys, orphaned by the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, that my great-grandparents raised.

The story has a couple parts.

First, the twins’ story as recounted via family oral history. My great-grandparents, John Peter and Amelia (Minnich) Lantz, were married in 1869 out east of Oswego in Will County’s Wheatland Township and began farming out on the rich prairie on the family home place. In March 1871, their first child, a boy they named Isaac, was born.

Back in that day, farming was physically demanding for both the farmer and his wife, who had to work in a true partnership to make a go of the operation. Those farm wives, especially, had a difficult life. Common household tasks we take for granted these days, such as washing clothes, were complicated and labor-intensive back then. As a result, most farm couples who lived on large acerages like my great-grandparents had not only hired men to help with farming but also hired girls to help in the house.

But my Pennsylvania Dutch ancestors on my mother’s side were a thrifty lot—cheap, according to my dad—and they were grimly determined to spend as little money as possible on just about everything. But with a new baby to take care of along with all her other regular chores, my great-grandmother began demanding help of some kind.

Along about 1872, my great-grandfather, prodded into eventual action by his increasingly adamant wife, headed off to Chicago. The Great Chicago Fire had swept through the city in the fall of the year their son was born, killing some 300 people and creating a number of new orphans who joined the growing number of parentless children in the city. My great-grandmother, hearing about the availability of orphans, sent her husband into Chicago with orders to bring back an orphan girl to help around the house.

My great-grandfather was a soft touch and a bit of a dreamer, the kind of guy who dabbled in gold mining stocks bought from ads in the back of magazines and newspapers with hopes of getting rich—hopes that were invariably dashed. So it shouldn’t have been a surprise that instead of coming home with an orphan girl to help his wife around the house, he ended up bring home two six year-old orphan boys, Tom and John Kelly.

Whether they were even actually orphaned by the great fire isn’t part of family lore but they were welcomed as part of the family, although I imagine somewhat grudgingly on my great-grandmother’s part.

The Kelly boys not only lived with my great grandparents, but by all accounts were treated like their own children. In fact, in the 1880 U.S. Census of Wheatland Township, Will County, they are both listed as my great-grandparents’ sons.

During that era, farm children were expected to work hard, both helping on their own family farms and also by being hired out to other families. Their daughter, my grandmother, for instance, was hired out to nearby families when she reached the age of 14. She had graduated eighth grade with good marks and had looked forward to attending high school—and even found a well-off Aurora family willing to offer her board and room in return for help around the house while she went to school, but my great-grandparents refused the offer and insisted she work for wages. Women, their feeling was, didn’t need an education.

So the Kelly boys, too, were hired out in their teens. The Sept. 20, 1883 Kendall County Record reported from Oswego that “Dr. Putt has gone to Nebraska; also John and Tom Kelly.” At that time they were 17 years old.

When they reached the age of 20, my great-grandparents gave each of them a new suit of clothes and $1,200—that’s nearly $40,000 in today’s inflation-adjusted dollars—in order to make their ways in the world. They apparently used the money to buy a farm out near Hastings in the southeastern corner of Nebraska where they’d gone with Dr. William T. Putt back in 1883.

Eventually, however, they came back to Illinois and worked on various farms around the Oswego and Wheatland Township areas, John dying in 1916 and Tom living until 1929. They’re both buried in the Wheatland United Presbyterian “Scotch” Church Cemetery out in Wheatland Township.

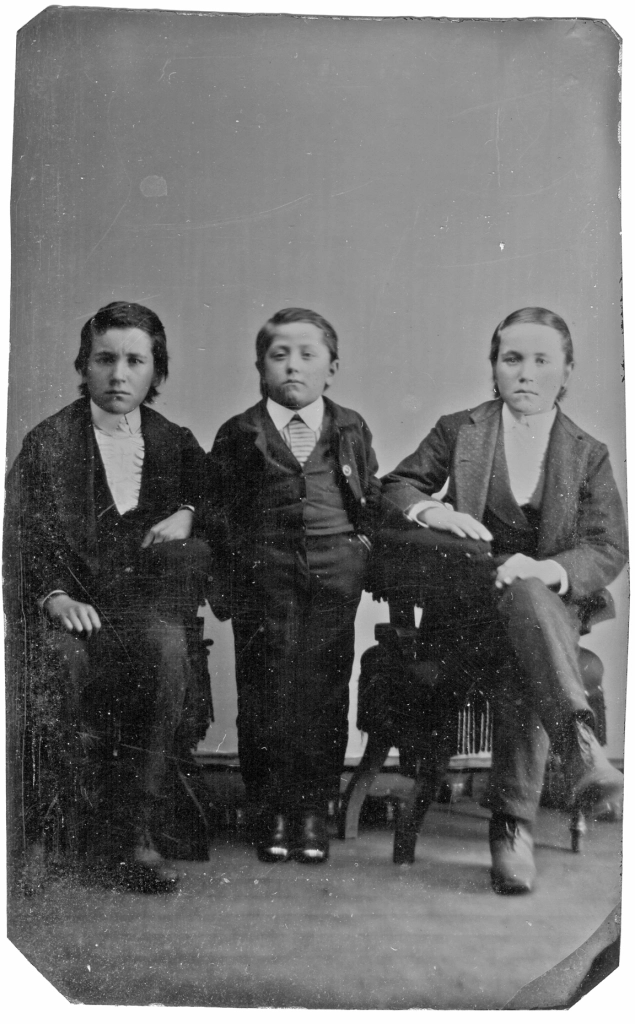

I’ve heard about the twins my entire life, as part of our family’s lore. Photos of the boys came down to me through my grandmother’s family, a couple tintypes and some cabinet photos. And their burial records are part of the collections at the Little White School Museum. But Tom Kelly’s snuffbox is the first tangible item I’ve ever seen that one of them actually owned and used.

Down at the museum, you just never know what interesting bit of local history will walk through the door to brighten your day.

The Matile Manse is located right on the Fox River Trail, a walking, running, and biking trail that extends from Oswego north all the way to the Wisconsin state line. It’s really nice to see so many people using it and seeming to have such a good time doing so. On a warm summer Sunday morning, I swear we see half of Oswego’s population walking, running, or biking on the trail. It’s certainly one of the most heavily used amenities in the Oswegoland area and we owe former Oswegoland Park District Executive Director Bert Gray and environmentalist, naturalist, author, and war hero Dick Young for doing all the deep spadework that made it a reality.

The Matile Manse is located right on the Fox River Trail, a walking, running, and biking trail that extends from Oswego north all the way to the Wisconsin state line. It’s really nice to see so many people using it and seeming to have such a good time doing so. On a warm summer Sunday morning, I swear we see half of Oswego’s population walking, running, or biking on the trail. It’s certainly one of the most heavily used amenities in the Oswegoland area and we owe former Oswegoland Park District Executive Director Bert Gray and environmentalist, naturalist, author, and war hero Dick Young for doing all the deep spadework that made it a reality.