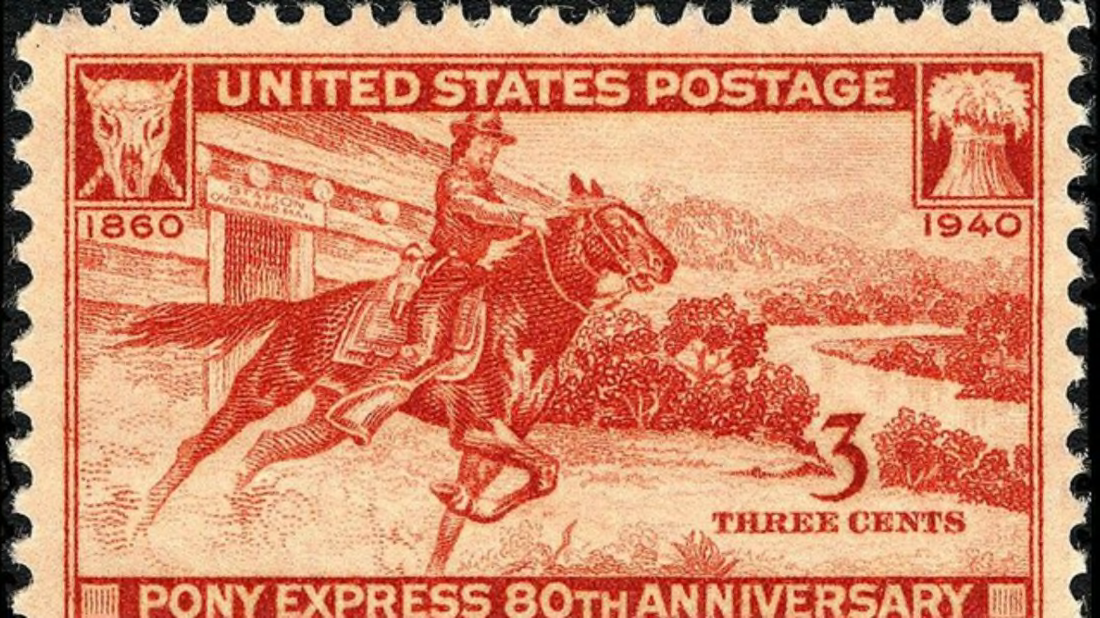

The Pony Express became the stuff of American legend, mostly thanks to William “Buffalo Bill” Cody and his world-famous Wild West shows.

Businessman William Russell established the Pony Express in April 1860 as a publicity stunt he hoped would help him win a contract to carry the U.S. Mail by stagecoach from Independence, Mo. to California. In reality, Russell’s ploy lasted only 18 months, and never carried the U.S. Mail. Rather Russell’s venture was a private express service. As one of his riders later put it, the Pony Express was a stunt, “a put-up job from start to finish.”

The Pony Express is one of the most enduring legends of the Old West. Unfortunately, most of the legend is historical bunk.

Despite the Pony Express’s short, ineffective run, thanks to Buffalo Bill (who as William Cody was one of the young men who rode for the company) and his entertaining wild west shows, the Pony Express has gone down in American history as a noble effort to provide speedy transcontinental communications. In fact, since 1907, it has been the subject of 15 movies, two made for TV movies, and a 1959 television series.

Although most of us seem to believe Russell’s effort was the first of its kind, people living at the time knew it was not. In fact, the U.S. Post Office itself ran a much more effective and heavily used Express Mail service that connected much of the nation during the 1830s. And unlike Russell’s PR stunt, it actually carried the U.S. Mail.

Designed primarily to carry financial news linking important, but far-distant cities in the West such as New Orleans and St. Louis with Eastern markets, the Express Mail had a couple branches. One of those Express Mail branches passed through our state of Illinois on the National Road (now U.S. Route 40), connecting Dayton, Ohio with St. Louis, passing through Vandalia, Ill.

John McLean, postmaster general, 1823-1829

Express Mail differed from the regular mail in that it was carried by a single man on horseback who was required to make the best time possible. Unlike the contracts for carrying the regular mail by stagecoach and wagon, Express Mail carriers could lose their contracts if they were late or missed a delivery.

Actually, Express Mail service was sporadically established at many times during the nation’s early history. Private express riders carried messages during the colonial period, then after the Revolution, most expresses were part of the military communications network.

The need for fast, universally available long-distance communications service became apparent in the spring of 1825. When a fast sailing ship arrived from England, New York cotton merchants, learned that cotton prices on the London market had skyrocketed. They then bribed the contractor carrying mail between New York and New Orleans to delay the news of the price jump. Meanwhile, the merchants rushed their buy orders to New Orleans ahead of the news so they could buy all the cotton they could find at low prices. When they sold the cheap cotton at the high prices in London, they made hefty profits. The cotton merchants who weren’t let in on the deal were not happy.

Postmaster General John McLean, who served from 1823-1829, vowed such a thing would never happen again, and prohibited mail contractors from carrying private messages “outside the mail,” meaning any messages carried by regular mail contractors, but not carried in the official portmanteau. During that era, the U.S. Mail was strictly defined as matter that was carried in the official portmanteaus, large canvas sacks with special locks. Mail contractors were threatened with loss of their contracts if they informally carried any messages that weren’t the mail. And that was a big deal, since without a mail contract, a stagecoach company simply couldn’t be profitable. In fact, at one time if a mail contractor lost his contract, he was obliged to sell his coaches, horses, and other equipment to the successful bidder.

In an effort to get the most important economic news delivered as quickly as possible, McLean decided to establish an Express Mail to travel what was called the Great Mail Line from New York to New Orleans. McLean’s expresses, however, only traveled a few times a year. It would be up to one of his successors to create a true Express Mail service.

Amos Kendall, postmaster general, 1835-1840

In 1835, Amos Kendall took over the job of Postmaster General for President Andrew Jackson following a scandal that erupted when Postmaster General William Barry, who was not only incompetent, but also allowed politics to enter the mail carriage contract system. Barry’s corrupt incompetence drove the previously financially healthy postal service into bankruptcy.

Enter Kendall—our county’s namesake. Kendall was a former Tennessee newspaper publisher and crony of Jackson who turned out to have a genius for organization. In taking over from the corrupt Barry, he instituted a wide range of reforms, which, combined with a nationwide financial boom created huge postal revenue surpluses.

Kendall decided to spend his newfound surplus cash on a comprehensive Express Mail service carrying regular mail and newspaper “slips” along the New York to New Orleans route. Regular mail was carried in the Express Mail at three times the normal postage, while newspaper slips (described as “small parts of newspapers, cut out, or strips specially printed…to convey the latest news, foreign, and domestic”) were carried free of charge from town to town to spread the news. During that era, newspapers were considered vital to the proper functioning of a democracy, and thus the government had an interest in seeing the news of governmental happenings was spread as widely and as quickly as possible. Quite a difference from today.

President Jackson signed Kendall’s bill creating the Express Mail into law in July 1836, and the service began that same autumn. Within a few weeks, another express route was added from Philadelphia to Mobile, Ala. In 1837, two Missouri legislators prevailed on Kendall to establish a branch of the Philadelphia to Mobile express that branched off from Dayton, Ohio to St. Louis. The Illinois state capital at Vandalia was on that branch line of the Express Mail.

Starting on Oct. 1, 1837, express riders traveled from Dayton to Richmond, Ind. and on to Indianapolis. From Indianapolis, the route ran 72 miles to its terminus at Terre Haute, Ind. Two months later, on Dec. 10, 1837, the route was extended across the 99 miles of prairie from Terre Haute to Vandalia, and from there, 65 miles to St. Louis. Each stage of the trip was made daily by express riders.

The daily expresses made a considerable difference in the time it took for news to make its way west. In 1835, it took letters an average of 11 days and 15 hours to get from New York to Vandalia. Thanks to the Express Mail, that time was cut by almost two-thirds to just 4 days 15 hours.

But by late 1838, the days of the Express Mail were numbered. Thanks to the accelerating pace of railroad construction and major improvements to the nation’s road system, the regular mail had become nearly as fast as the express riders. As a Louisville, Ky. newspaper put it in 1838: “The rapidity with which the ordinary mail now travels from New York…makes it practically an express without the charge of triple postage.”

While overland travel was quickly improving the speed of the mails, the nation was also on the cusp of a telecommunications revolution that would, in less than a decade, supersede all existing communications technology. Samuel F.B. Morse invented his electric telegraph in the 1830s, and had largely perfected by 1845. In March of that year Morse and his partner Alfred Vail hired none other than former Postmaster General Amos Kendall (who’d left government service in 1840) to manage their business. Kendall, no fool he, agreed to work for a ten percent stake in the new company, which he incorporated as the Magnetic Telegraph Company. The expansion of telegraph service throughout the nation soon meant that spreading vital economic information was no longer limited to the speed of a horse, but could instead speed along copper wires. It revolutionized communications—which it continues to do to this day.

And Kendall had a hand in that success. After leaving the post office, he tried journalism and went broke (not uncommon even today) and was nearly a subject for debtor’s prison when Samuel F.B. Morse and his partner, Alfred Vail, decided to hire Kendall as their business manager to manage the business of promoting their new telegraph invention. It turned out to be a genius move as Kendall turned his organization skills to promoting the telegraph. And tt ended up making Kendall a multi-millionaire.

Kendall’s Express Mail, as a stopgap while the nation improved its transportation infrastructure and communications technology, was a success, keeping the nation tied together via the most sophisticated information technology the era offered. And it might be interesting to note that sending a one-page letter by Express Mail from New York to Vandalia here in Illinois in 1837 cost 75 cents—a time when land in Illinois was selling for $1.25 per acre. That certainly puts our seemingly endless modern postal rate increases into some historical perspective.