Another Memorial Day has rolled around, this time with the nation in actual peril, thanks to a new highly contagious disease, for the first time in a many years.

Procession marching through downtown Oswego on Decoration Day, around 1910. Parade Marshal George White leads the parade, which usually consisted of a marching band, civic and fraternal organizations, and citizens. When the procession reached the Oswego Township Cemetery, a short memorial service was held for the community’s Civil War dead, after which Oswego school children decorated the graves of deceased veterans with flowers.

Originally established to honor the graves of Civil War soldiers and so named Decoration Day, today’s Memorial Day honors all the nation’s military personnel who have died.

As wars go, the Civil War has never been my favorite area of historical study. Better named the War of Treason in Defense of Slavery, the war pitted the largely rural Southern states against the North and its mix of rural and industrialized urban areas. Both sides were unlucky in the military commanders they chose to lead the fight against the other side. It took a few years before the North’s crop of military leaders was finally distilled down to no-nonsense men like Ulysses Grant and William Sherman, Grant invaluable because of his grasp of strategy and Sherman for his tactical brilliance. Meanwhile, the South chose Robert Lee as their military leader, a man whose grasp of the kind of strategy required to defeat a stronger foe was disastrously flawed. The result was more than 600,000 killed in action, dead of wounds, and perished from disease.

Here in Kendall County, more than 10 percent of the total population went off to fight and the war’s lasting effect was to see the county’s population steadily decline for the next century until it finally surpassed its 1860 total in 1960.

But while the South was soundly beaten militarily during the war, it immediately began fighting to win the peace, which it did. Reinstituting the terrorism that had kept the South’s slave population in line, the Jim Crow era was, if anything, even more violent than slavery itself. And the South’s efforts to redefine the cause of the war was just as successful. By the time I was in high school a century after the war was fought, we were taught that the underlying cause of the war was state’s rights. Slavery, we were told, was a dying institution at the time and would have ended had the war never been fought.

Neither of those were true. The war was mainly fought over the South’s continuing, and increasingly unsuccessful, efforts to expand slavery into the new territories being brought into the Union. All of the existing resolutions of secession passed by Southern state legislators mention the North’s attitude towards slavery as a major cause, if not the major cause, of the states’ secession. Union. And as for being on the way out, slavery was financially lucrative in the extreme. In fact, the value of all the South’s slaves was more than the value of all of the North’s industrial, railroad, and banking facilities.

As for the Civil War itself, a little over a century and a half ago this month, the conflict was in full swing with the ultimate result still very much in doubt.

While the Union was still convinced it could defeat the rebellious secessionists if just given a little more time, reality was staring to intrude. It would take more years of blood and treasure to finally stamp out the rebellion begun by the South’s pro-slavery forces.

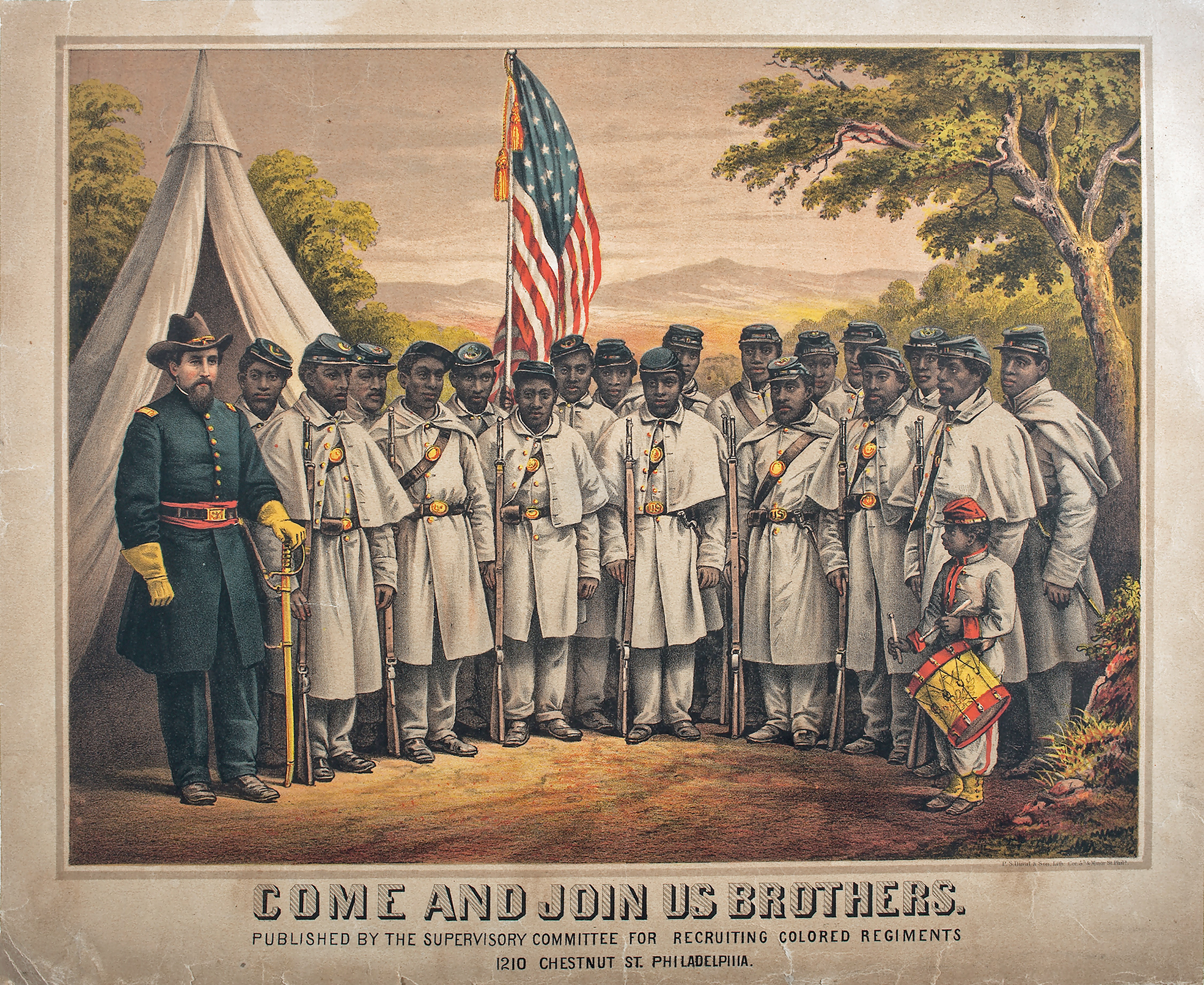

It would also take a lot more soldiers—by 1864, the Union was scraping the bottom of the personnel barrel. But there was an as-yet untapped resource: thousands of black men who were already living in the North and areas in the South controlled by the U.S. Government. Some were Northern-born and wanted to fight; others had escaped from slavery and were eager to do their part to ensure freedom for everyone in the nation.

Many blacks were already serving in support roles as teamsters and other noncombatant jobs. Others were serving in combat with state units, such as the famed 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, the subject of the film, “Glory.” But on May 22, 1863, with the number of potential soldiers drying up across the North, the War Department issued General Order 143, establishing the United States Colored Troops. Regulations called for all officers to be white, although non-commissioned officers—corporals and sergeants—were to be promoted from the ranks.

However, some light-skinned blacks passed for white in order to serve as officers, like William N. Reed, a New York abolitionist. Reed graduated from the German military school at Kiel and had served in the German army. Arriving back in the U.S. he managed to obtain a commission as colonel of the 1st. North Carolina Colored Infantry Regiment, later reorganized as the 35th U.S. Colored Infantry. Reed is recognized as the highest-ranking African American in the Civil War

Illinois Gov. Richard Yates began raising a regiment of colored troops late in 1863, but the early efforts were slow, due to a combination of factors including lower pay for black soldiers and the brutal treatment black prisoners of war received at the hands of the rebels. But gradually the regiment’s companies were filled with volunteers from all over the state until it was ready to be formally accepted for service at Quincy on April 24, 1864.

Illinois Gov. Richard Yates began raising a regiment of colored troops late in 1863, but the early efforts were slow, due to a combination of factors including lower pay for black soldiers and the brutal treatment black prisoners of war received at the hands of the rebels. But gradually the regiment’s companies were filled with volunteers from all over the state until it was ready to be formally accepted for service at Quincy on April 24, 1864.

Although U.S.C.T. (U.S. Colored Troops) regiments were not always fortunate in their commanders, the 29th was, with Lt. Col. John Bross of Chicago, a skilled, knowledgeable veteran, in command. The regiment was assigned to the Fourth Division, IX Corps of the Army of the Potomac, the first black division to serve with the Union in the Virginia theater.

Among those who enlisted in the 29th, was an escaped slave named Nathan Hughes. According to his military records, Hughes was born in Bourbon County, Ky. and was, according to his family’s tradition, of mixed black and Seminole ancestry. Like many slaves, he was apparently unsure of his birth date. His military records stated he was 33 when he enlisted in 1864, making his birth year 1831. However, his family had a birth date of 1824 inscribed on his tombstone.

Whatever his age, Hughes managed to escape slavery, but in doing so was forced to leave his family behind. Reaching Illinois, he apparently settled near Yorkville and worked as a laborer until he volunteered for service in the 29th, enlisting in Company B under Capt. Hector Aiken.

While the 29th was fortunate in its commanding officers, it was not so lucky in those assigned to command the Fourth Division, nor the IX Corps to which it was assigned. Gen. Edward Ferrero the division commander, was a former dance instructor of middling ability, and the corps commander, Gen. Ambrose Burnside, was better but no military genius. After reaching the Virginia front where Union forces besieged the rebel capital of Richmond, the 29th was assigned to protect the Union Army’s supply lines, participating in a number of skirmishes. On May 9, 1864, the 29th was instrumental in throwing back a determined rebel assault on some vital Union supply convoys.

After Gen. Ulysses Grant took command of the Union armies, he orchestrated a campaign designed to destroy the main rebel force, the Army of Northern Virginia, using a series of flanking movements gradually forcing the rebel army back on the Confederate capital of Richmond, Va. Richmond was not only valuable as the rebel capital, but also because of its industrial facilities and its position as a rail hub—the Civil War was the first railroad war and the lines were vital to supply the huge armies involved.

But the siege of Richmond was not something Grant wanted. He had pursued rebel Gen. Robert Lee in a series of hard marches and battles through the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor unsuccessfully trying to corner him before Lee was run to ground in the extensive defensive works around Richmond.

Grant knew the heavily fortified Richmond suburb of Petersburg was the key to the rebel position, but could see no way to break into it. While Lee was a good tactician and a middling strategist, he was a fine military engineer.

This detail from a Tom Lovell painting shows the ferocious combat that took place between rebel troops and United States soldiers during the Battle of the Crater at Petersburg, Virginia.

So the two armies, the Union Army of the Potomac and the rebels’ Army of Northern Virginia settled down in a siege neither side wanted. Enter the coal miners serving in the Union Army’s 48th Pennsylvania Infantry, who proposed to dig a tunnel under the rebel works. The idea was to hollow out a large open cavern under the rebel fortifications, fill the cavern with gunpowder, and blow up the rebel works. The mine was completed, the charge blown up, and a huge break in the rebel lines was created. But the Union assault was a confused failure, thanks to incompetent commanders. The Battle of the Crater that took place as Union troops, including Ferrero’s U.S. Colored Troops, attempted to exploit the new break in the rebel lines was depicted from the Southern point of view in the 2003 film “Cold Harbor.” It was a Union disaster.

The 29th U.S. Colored Infantry was one of the regiments that were part of the assault force, and during the melee, Nathan Hughes was badly wounded, shot in his left knee. He must have been a tough guy because unlike so many Union soldiers, Hughes survived the serious wound, including being sent to a military hospital. He not only survived but was returned to duty months later, just in time to be wounded again, this time less seriously in the hand. Doing hard marching with the 29th, Hughes fought through the battles and skirmishes of Boydton Plank Road, Globe Tavern, Poplar Grove Church, and Hatcher’s Run before Grant was able to bring the Army of Northern Virginia to bay at Appomattox Courthouse, Lee’s surrender in April 1865 effectively ending the war. The 29th was then sent down to Texas to watch the border with Mexico thanks to French meddling with that country while the U.S. was distracted with its internal conflict. The regiment was mustered out of U.S. service in November 1865.

After being mustered out with the rest of the regiment in Texas, Hughes returned to Illinois where he decided to settle on a small plot in Kendall County near Oswego on today’s Minkler Road. Like many escaped slaves forced to leave their families behind during their desperate flight north, Hughes headed back to Kentucky after the war to try to retrieve his wife and children. His three children decided to go back north with their father. His wife, for whatever reason, decided to stay in Kentucky. It must have been a wrenching decision to watch her children leave, but it must also have been an almost impossible choice for those who had been considered property only a few months before to make another such momentous change in their lives. I suspect the PTSD suffered by former slaves, as well as many of the men who served during the war, was a real burden for thousands for many years after the war.

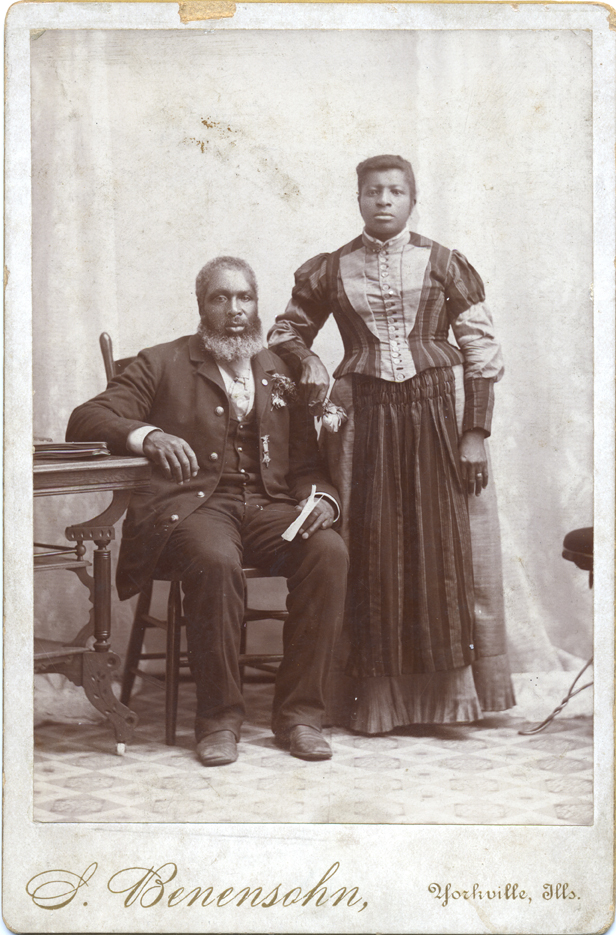

In 1893, Yorkville photographer Sigmund Benesohn took this portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Nathan Hughes. Hughes is proudly wearing his Grand Army of the Republic lapel pin. Confederate Army canons were melted down to make the pins. (Little White School Museum

Nathan Hughes came back to the Oswego area with his children, eventually remarried and lived for the rest of his life on his small farm on Minkler Road southwest of Oswego. He was a respected member of the farming community there, and was the only Black member in Kendall County of the Grand Army of the Republic, the Union veterans’ organization, where he served as an officer of the GAR’s Yorkville post.

His children married into the nearby Black farming community, most members of which eventually moved into Aurora where jobs in the city’s many factories were more attractive than the labor-intensive, low income farming of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His descendants prospered, two of his grandchildren becoming the first Black male and first Black female to graduate from high school in Kendall County (both from Oswego High School). And their descendants prospered, too, becoming elementary and high school teachers, and college professors—and at least one Federal judge.

Hughes died in March 1910, and was buried in the Oswego Township Cemetery, where he lays today with four of his black Civil War comrades. Wrote Kendall County Record Publisher John R. Marshall—himself a Civil War veteran—upon Hughes’s death: “It is a pleasure to bear testimony to his worth as a man and a patriot; he was loyal to his country and in all his associations was a quiet, self-possessed man of the best of traits… A good citizen, he has left a vacant place in the ranks of the ‘boys in blue.’”

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, John Steward of Plano decided this climactic battle took place Maramech Hill near Plano here in Kendall County. Armed with this conviction and a good deal of money, he set out to find information to prove his contention. In 1903, Steward published a book he felt proved his point, Lost Maramech and Earliest Chicago, and even had a huge rock moved to the hill and inscribed with his version of what be believed transpired there.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, John Steward of Plano decided this climactic battle took place Maramech Hill near Plano here in Kendall County. Armed with this conviction and a good deal of money, he set out to find information to prove his contention. In 1903, Steward published a book he felt proved his point, Lost Maramech and Earliest Chicago, and even had a huge rock moved to the hill and inscribed with his version of what be believed transpired there.

Finally, thanks to the area’s topography, today the Maramech Hill area is also one of Kendall County’s natural jewels featuring rare and endangered plants, a startling variety of wildlife, and unique geographical features.

Finally, thanks to the area’s topography, today the Maramech Hill area is also one of Kendall County’s natural jewels featuring rare and endangered plants, a startling variety of wildlife, and unique geographical features.