A bit of area history came to an end on April 27 when the Illinois Department of Transportation announced the closure of the intersection of U.S. Route 30 and Harvey Road in northeast Oswego Township.

Since the construction of Oswego East High School just off Harvey Road, the angled intersection had become the site of accidents and near-misses so it made sense to close it and redirect traffic to the signalized intersection at Treasure Drive just a short distance east of Harvey Road. Instead of joining Route 30, Harvey Road will now end in a cul-de-sac.

Since the construction of Oswego East High School just off Harvey Road, the angled intersection had become the site of accidents and near-misses so it made sense to close it and redirect traffic to the signalized intersection at Treasure Drive just a short distance east of Harvey Road. Instead of joining Route 30, Harvey Road will now end in a cul-de-sac.

How did that intersection come to be the way it is today? Well, the road used to go straight past Lincoln Memorial Park and down modern Harvey Road. That’s back when the road from Aurora was called the Lincoln Highway, the nation’s first marked coast-to-coast road. A few years later, when the highway was paved and became U.S. Route 30, its route diverged making the modern curve to follow the right-of-way of the Elgin, Joliet & Eastern Railway and the Joliet, Plainfield & Aurora interurban trolley line. The right-of-way for that change of course for the 2.5 miles in Kendall County, starting at Harvey Road, was purchased by the Kendall County Board using a donation from the good roads folks in Aurora and then given to Illinois to speed paving the highway.

So what’s the story behind the Lincoln Highway itself?

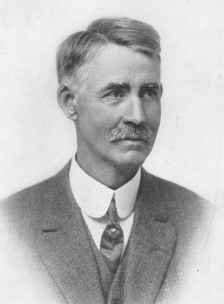

In 1913 Carl Fisher was a man with a vision. The Indianapolis daredevil auto racer, showman, and entrepreneur figured that what the United States needed to spur business and hasten the development of the automobile was a transcontinental highway linking the Atlantic shore with the Pacific coast.

Fisher worked hard to drum up private support for what he called a “Coast to Coast Rock Highway,” so named because it was not to be just a marked route, but was to be one with a good gravel surface that would theoretically allow travel in all weather.

Fisher’s campaign was far from a slam-dunk, however. Henry Ford for instance, a guy you’d think would have jumped at the idea as a way to sell more of his Model T’s, disdained the whole notion, holding out for government funding for major roads, not private financing. Ford, of course, had a point. But at the time Fisher was militating for his coast-to-coast highway, government funding for such a project was simply not in the political cards. But Fisher persisted, and the pledges of support started rolling in, especially after he renamed the proposed interstate road after one of his heroes, Abraham Lincoln.

In June 1913, Fisher incorporated the Lincoln Highway Association at Detroit, Mich., with Henry B. Joy, president of the Packard Motor Company, as its president and Fisher serving as vice-president.

At the time of incorporation, in fact, Joy was westbound with a caravan of Packards and their owners, blazing what he considered the most direct route west to California.

By October, the association settled on the Lincoln’s main course, making use of existing roads along most of the route’s 3,389 miles. They announced the route to the public on Oct. 26, 1913 at a meeting of the governors of the 13 states through which the new highway would run. As planned, the Lincoln started at the corner of Broadway and 42nd Street at New York City’s Times Square, then headed west into New Jersey and then through to Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, and California, where the terminus was established in San Francisco just outside today’s Legion of Honor Museum in Lincoln Park just off Geary Boulevard at 34th Street.

The Lincoln Highway was formally dedicated on Oct. 31, 1913.

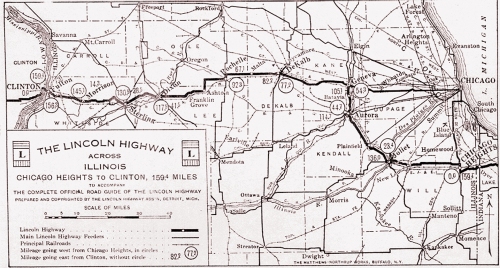

This 1924 map traces the original route of the Lincoln Highway–now U.S. Route 30–through Illinois from Indiana to Iowa.

As it was envisioned and designed, the highway bypassed major cities in favor of traveling through medium-sized towns and villages. Here in Illinois, it bypassed Chicago, looping south around the city through Joliet, Plainfield, on through a portion of Wheatland Township in Will County and Oswego Township in Kendall County, before reaching Aurora. The original route passed Phillips Park on modern Hill Avenue, where, in 1923, the Lincoln Highway Pavilion was built by the Aurora Automobile Club. I remember having family gatherings in the pavilion when I was a child. Completely restored a few years ago, the pavilion still exists, easily seen off Hill Avenue, the old Lincoln route near Phillips Park’s Hill Avenue entrance.

The Lincoln Highway Association marked the route of the Lincoln Highway with red, white, and blue badges.

In Wheatland and Oswego townships, the road followed a winding course on existing country roads. Most of the original route has been marked by the Illinois chapter of the Lincoln Highway Association, so if you’re of a mind, you can travel that road today by following the signs east from Aurora.

But as more and more traffic surged onto the new highway, officials started looking to both simplify it’s course and to pave it. With so many twists and turns between Plainfield and Aurora, that section of the Lincoln was an obvious choice for revision. So in 1923, with the promise by Illinois officials to pave the route as soon as possible, the Kendall County Board voted to acquire 2.5 miles of right-of-way paralleling the Elgin Joliet & Eastern Railroad and the Joliet, Plainfield & Aurora Transportation Company’s interurban line.

As the Feb. 14, 1923 Kendall County Record explained: “The new right-of-way in Kendall county for the Lincoln highway is necessitated by a relocating of the route to shorten the distance between Plainfield and Aurora.”

The Lincoln Highway Shelter on the highway at Philips Park in Aurora was built for camping auto travelers in 1923 by the Aurora Automobile Club. Completely restored a few years ago, it’s a living reminder of the highway’s glory days.

Spurred on by the promise of quick action in Springfield, Kendall County officials were moving quickly. The policy at that time was that local government was responsible for obtaining highway rights-of-way, and then the state would cover the costs of engineering and construction. That spring, Gov. Len Small promised that if the right-of-way was procured at once, he’d add the Plainfield-Aurora section of the Lincoln to the 1923 highway program, along with the even more eagerly sought paving of Route 18, The Cannonball Trail Route (now U.S. Route 34).

Kendall County taxpayers, however, were not totally on the hook for the cost of the land. The Good Roads Committee of the Aurora Chamber of Commerce raised $1,000 in donations from city residents to defray Kendall County’s costs. “The money [for the right-of-way purchase] was all donated in Aurora,” the Record noted on March 14.

It was about this same time that the old system of giving highways names—such as the Lincoln Highway, the Dixie Highway (another of Fisher’s creations), and The Cannonball Trail—was being phased out in favor of a system of numbered routes that were government-funded. In general, east-west routes were given even numbers, while north-south routes got odd numbers. The system wouldn’t go nationwide until 1926, but by then it had already begun in Illinois. The Lincoln, for instance, was first designated Route 22 by Illinois. The Cannonball Trail, linking Chicago with Princeton via Naperville, Aurora, Oswego, Yorkville, Plano, and Sandwich, was initially numbered Route 18.

It’s remarkable how quickly things moved during that era, especially compared to the glacial pace at which modern highway projects advance. On May 9, 1923 the Record reported: “The Chicago Heights Coal Company of Chicago Heights was the lowest bidder for paving sections 15 and 16, Route 22, Lincoln Highway, commencing at Plainfield and running west to Aurora, a distance of 5.19 miles, when the bids were opened at Springfield April 13. Its bid was $222,000.”

The last unpaved local section of U.S. Route 30 was finished in 1936 when the cloverleaf intersection with U.S. Route 34 was built with federal WPA funds. (Little White School Museum collection)

In early June, the Plainfield Enterprise reported state officials were promising that all 159.4 miles of the Lincoln Highway in Illinois would be paved during 1923. And, apparently, it was. The only remaining gravel stretch of the highway in Kendall County was at its intersection with Route 18—today’s Route 34. With delays and then the advent of the Great Depression, completion lagged. It required federal Works Progress Administration funds to complete the Route 30-34 cloverleaf intersection and overpass, which wasn’t finished until 1936.

In November 1926, the states officially approved the federal government’s new numbering system, part of which designated the Lincoln as U.S. Route 30 along its entire length and Route 18 as U.S. Route 34.

Despite the advent of the interstate highway system, the Lincoln Highway still carries hundreds of thousands of cars, trucks, and buses along its transcontinental length daily more than a century after Carl Fisher spearheaded its development, another living reminder of our area’s transportation and economic history. And with the closure of the Route 30–Harvey Road intersection, a bit of that history has added one more bit to the story of the Lincoln Highway.

The Wisconsin Glacier was the last of these advances, and as it slowly advanced, it bulldozed and abraded the landscape right down to the bedrock, then briefly retreating before moving forward again, leaving a variety of glacial landforms behind from kames (irregularly shaped sand, gravel and till hills or mounds that accumulates in a glacial depression) to eskers (long, winding ridges of stratified sand and gravel) to moraines (an accumulation of debris ranging in size from silt-sized glacial flour to large boulders created by glacial action).

The Wisconsin Glacier was the last of these advances, and as it slowly advanced, it bulldozed and abraded the landscape right down to the bedrock, then briefly retreating before moving forward again, leaving a variety of glacial landforms behind from kames (irregularly shaped sand, gravel and till hills or mounds that accumulates in a glacial depression) to eskers (long, winding ridges of stratified sand and gravel) to moraines (an accumulation of debris ranging in size from silt-sized glacial flour to large boulders created by glacial action).