Kendall County was no stranger to influenza in the years before 1918. Back in those pre-World War I days, though, they called the grippe.

On Jan. 1, 1890, Lorenzo Rank, the Kendall County Record’s Oswego correspondent, reported that a newly-named sickness had arrived: “There are two or three new cases of sickness, but merely of the ordinary and domestic kind–none of the new style and imported ‘La Grippe’ in town.”

Over the next decade, waves of the grippe—it’s name quickly simplified to the grip—passed through the community, and its annual presence became fairly commonplace. But the seriousness of the occasional waves seemed to be getting greater as the years passed.

In late December 1915, the Record reported from Yorkville that: “An epidemic of the grip has prevailed in this section for the past month and efforts are being made to stop the infection. Chicago is taking radical measures and every home should take precautions.”

“There is a report that a grip siege is passing over this continent and NaAuSay seems to be directly in its path as many are afflicted with the dread disease,” the Record’s NaAuSay correspondent added on Jan. 5, 1916.

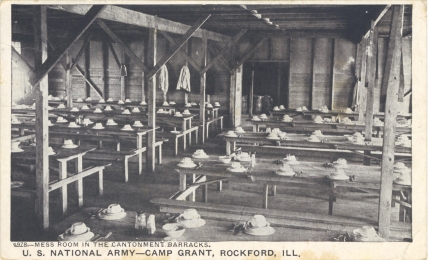

A mess hall at Camp Grant was pictured on this postcard, illustrating the close quarters the soldiers undergoing training lived in. Hundreds of recruits were afflicted with the Spanish Flu there in 1918.

Scattered outbreaks of the grip continued through 1916 and 1917. Then in October of 1918 a newer, deadlier strain of respiratory illness—this time more accurately dubbed influenza—made its appearance in Kendall County. By that time, the nation was deeply involved in World War I, with hundreds of young Kendall County men heading off for basic training, most to Camp Grant near Rockford.

Little did area residents know that an extremely virulent and deadly strain of the H1N1 influenza virus had mutated into a far more aggressive and deadly variety than ever experienced before.

The nationwide outbreak started in the summer of 1918 as Navy and merchant ships brought the disease—which had, ironically, actually evolved in Kansas the year before—back to the U.S. after it began ravaging Europe. It was dubbed the Spanish Flu because the press in Spain—which was a neutral in the war—was unhindered by wartime censorship in its coverage of the disease. That meant the only news about the disease was coming from Spain and thus the name. And, in fact, the U.S. and other governments at war were mightily trying to keep the seriousness and extent of the disease as secret as they could. Unfortunately for them—and for the millions who would eventually die from it—it soon became impossible to deny what was happening.

Here in Kendall County, the first case of the new influenza was reported in the Record’s “Oswego” news column on Oct. 2, 1918: “Mr. and Mrs. Harold Russell attended the funeral of her cousin, Howard Byers of Sandwich. He had just received the commission as lieutenant when he was taken ill with Spanish influenza, living but a few days.”

That initial mention included some troubling foreshadowing. First, Byers was a healthy young man. Previous episodes of the grip had largely affected older, less healthy adults. Second, and more ominously, Byers died very quickly

Meanwhile, at the county seat of Yorkville, schools were being affected: “The epidemic of influenza struck the Yorkville high school last week and that branch of the school was closed on Thursday to reopen Monday,” the Record also reported on Oct. 2. “The teachers afflicted are Misses Hatch, Keith, and Klindworth. Superintendent Ackerman says if present conditions prevail, there is no cause for worry as to the rest of the school.”

But in reality, there was plenty of cause for worry.

The very next week, the Record reported: “The influenza has a firm grip on the country but it is gradually being shaken off, say the authorities. Advice offered to everyone is to be careful of that cold or any symptom promising the ‘flu.’ The death rate in this country has been heavy. People have been dying in large numbers in both civilian and official life. The only way to keep the country from a more serious epidemic is to use care in your health.”

Chief Gunner’s Mate A.N. Fletcher’s tombstone in the Elmwood Cemetery in Yorkville. Fletcher and his wife both died of the Spanish Flu at the Navy’s submarine base in New London, Connecticut.

That was easier said than done because the disease struck so quickly and was so deadly. That it respected no boundaries of any kind was illustrated by another story in that week’s Record when the death of Record editor H.R. Marshall’s brother-in-law, Chief Gunner’s Mate A.N. Fletcher and his wife at the submarine base hospital at New London Conn. was revealed. The official cause of their death was listed as pneumonia, but that was often an official euphemism for the flu insisted on by government officials trying to minimize the epidemic’s seriousness. At the time of his death, Chief Fletcher was instructing recruits in gunnery at the New London submarine base. His body was returned to Yorkville for burial. The Marshalls had no idea their family members had even been ill until they were notified of their deaths.

The disease was also hitting recruits at Camp Grant hard. There were so many influenza deaths, in fact, that the Army had to import morticians from around the country to process the bodies. Again, the government tried to keep a lid on exactly how bad things were, but a close reading of local news in community weeklies gave the game away.

Oswego’s Croushorn Funeral Home was operated by undertake George Croushorn. (Little White School Museum collection)

For instance, on Oct. 9, the Record reported from Oswego that: “[Undertaker] George Croushorn is at Leland, where he is substituting for Jake Thorson who has been called to Camp Grant to care for the bodies of pneumonia victims,” adding the significant news that “Otto Schuman of Fairbury, Nebraska, spent an hour in Oswego Tuesday. Mr. Schuman was born in Oswego and in early years moved to Nebraska. Owing to scarcity of undertakers he was sent to Camp Grant by the government.”

Sitting at his desk in the Record office in downtown Yorkville, Marshall seemed at his wit’s end, writing on Oct. 23: “The epidemic of influenza has knocked the bottom out of all social and business affairs. Its spread had caused the stopping of all congregations for any purpose and public gatherings are claimed to be a menace to health.”

The local deaths were joined by those from all over the nation. Out in Ottumwa, Iowa, local grocer Frank Musselman (my wife’s grandfather), just 34 years of age, died on Oct. 27, 1918, one of five young Ottumwa men to die that day. All five are buried near each other on a steep hillside in the Ottumwa Cemetery.

The flu epidemic gradually burned itself out—mostly—although there were still many more more deaths to suffer.

Looking back at that pandemic of more than a century ago, it’s hard not to compare it to what seems to be developing with the current coronavirus outbreak. Although officials are not yet labeling it a pandemic, it is clearly spreading at a terrific rate throughout the world. The U.S. government again seems to be concentrating on downplaying the outbreak’s seriousness, although this time they don’t have wartime security to blame. Instead, the disease’s spread and efforts to slow it—medical officials say it cannot be stopped, only slowed—seem to be soft-pedaled for purely political reasons.

One of the main reasons we study history is so that we can learn what works and what doesn’t so that we don’t keep making the same mistakes over and over again. Unfortunately, we no longer seem to learn from mistakes. Instead, these days the fashion seems to simply deny any mistake happened in the first place and go on our merry way.

The Spanish Flu of 1918 ended up killing tens of millions of people around the world. We now have the means to stop that from happening again. The question will be whether anyone in positions of responsibility has any idea how to make use of those means. Here’s hoping competence wins out over political expedience.

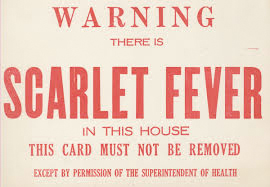

For county residents, I found quarantine first mentioned in a March 3, 1886 Record note when correspondent Lorenzo Rank reported from Oswego: “One of Kilbourne’s little girls became affected with the scarlet fever, a very mild case, however, the early part of last week. The family are boarders at Mrs. Teller’s, and that house has been somewhat quarantined. Miss Cox, one of our teachers, who also boarded there, for the reason of precaution immediately changed her place to Mrs. Moore’s.”

For county residents, I found quarantine first mentioned in a March 3, 1886 Record note when correspondent Lorenzo Rank reported from Oswego: “One of Kilbourne’s little girls became affected with the scarlet fever, a very mild case, however, the early part of last week. The family are boarders at Mrs. Teller’s, and that house has been somewhat quarantined. Miss Cox, one of our teachers, who also boarded there, for the reason of precaution immediately changed her place to Mrs. Moore’s.” Under the headline “Kendall County Cattle Quarantined,” the Record reported in its Nov. 11 issue: “The spread of the dreaded hoof and mouth disease that has been gaining serious proportions in Chicago and vicinity has brought it into Kendall County and up to Monday morning several herds of cattle had been quarantined. This disease has been prevalent in Europe for a number of years, has been noted in the United States but eight times and never before in Illinois. As a result of the visitation nearly all the northern counties of the state have been placed under quarantine, the Chicago stockyards closed and stringent methods have been adopted by the state veterinarian. Where a case is found in a herd of cattle they are segregated, killed, and the bodies either burned or destroyed with quick lime.”

Under the headline “Kendall County Cattle Quarantined,” the Record reported in its Nov. 11 issue: “The spread of the dreaded hoof and mouth disease that has been gaining serious proportions in Chicago and vicinity has brought it into Kendall County and up to Monday morning several herds of cattle had been quarantined. This disease has been prevalent in Europe for a number of years, has been noted in the United States but eight times and never before in Illinois. As a result of the visitation nearly all the northern counties of the state have been placed under quarantine, the Chicago stockyards closed and stringent methods have been adopted by the state veterinarian. Where a case is found in a herd of cattle they are segregated, killed, and the bodies either burned or destroyed with quick lime.” The very next week, the Record reported: “The influenza has a firm grip on the country but it is gradually being shaken off, say the authorities. Advice offered to everyone is to be careful of that cold or any symptom promising the ‘flu.’ The death rate in this country has been heavy. People have been dying in large numbers in both civilian and official life. The only way to keep the country from a more serious epidemic is to use care in your health.”

The very next week, the Record reported: “The influenza has a firm grip on the country but it is gradually being shaken off, say the authorities. Advice offered to everyone is to be careful of that cold or any symptom promising the ‘flu.’ The death rate in this country has been heavy. People have been dying in large numbers in both civilian and official life. The only way to keep the country from a more serious epidemic is to use care in your health.”