Oswego’s grown a LOT during the past several years, to the point that unincorporated Boulder Hill, once several times larger than the village, can now perhaps be considered a sort of suburb. But the time was, more than a century and a half ago, Oswego actually did have a suburb, and an industrial suburb of sorts at that, bordering the village to the north.

The Fox River Valley’s pioneer millwrights, who provided some of the most vital services early pioneers required, followed closely behind the area’s first settlers. Early millers used their talents to provide food by grinding corn and wheat into flour, and also supplied building materials from their first rudimentary saw mills on the Fox River as well as on its tributary creeks.

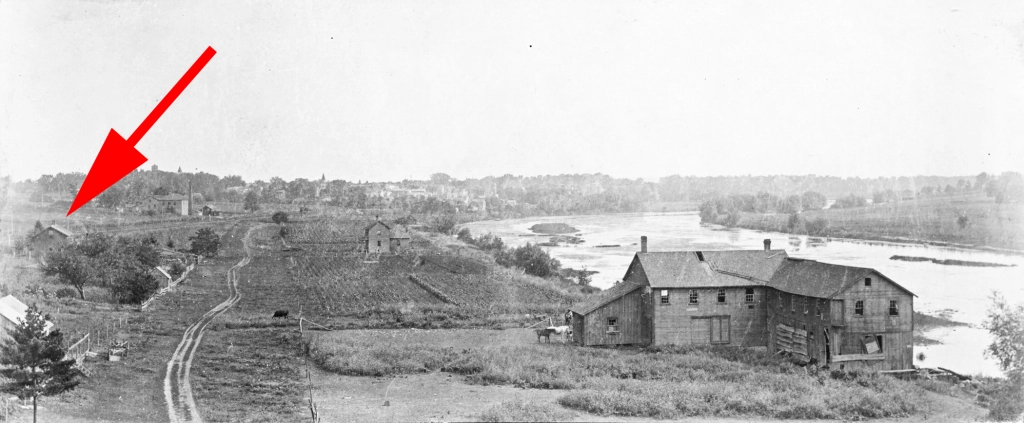

In 1836, Merritt Clark arrived in the Oswego area—the tiny village tumbling along the brow of the ridge overlooking the Fox River was then called Hudson—and built what Kendall County’s first historian called a corn mill on the west bank of the river. The mill was located about 3/4 miles north of the village that had been laid out in 1834 by Lewis B. Judson and Levi Arnold. Judson and Arnold called their new community Hudson—probably to remind them of their home area of New York—but it was renamed Oswego in 1837 after Congress awarded the growing town its own post office.

The same year Oswego got its post office, Levi Gorton and William Wormley built a dam across the Fox River to provide water power for Clark’s mill, and Clark reportedly added a chair factory to his corn milling operation. Later that same year, however, Clark apparently sold his business, including the mill and dam, to Levi Gorton and his brother, Darwin. The Gortons, apparently unsatisfied with Clark’s rudimentary mill, started construction that year of a true grist mill on the same site. The new mill was ready for operation the following year.

Then sometime prior to 1840, the Gortons sold their mill and dam to local business and property owner Nathaniel A. Rising. Rising and his partner, John Robinson, added a store to the grist mill at the west end of the dam and continued and apparently increased the business the Gortons had founded.

In 1848, apparently looking for even more opportunities, Rising and Zelolus E. Bell, who was then acting on behalf of the estate of the now-deceased Robinson, laid out the Town of Troy on a site located at the east end of the mill dam. The official plat of the new village was recorded on June 24, 1848 at the Kendall County Courthouse, then located in Oswego. County voters had agreed to relocate the county seat from Yorkville to Oswego in 1845.

Rising and Bell located Troy just far enough north of Oswego that the boundaries of the two towns never really touched each other, even after Walter Loucks’ addition to Oswego was platted sometime after 1860.

As laid out, Troy was bounded by Summit Street (now Ill. Route 25 and North Madison Street) to the east and the Fox River to the west. As originally numbered, the village consisted of Blocks 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 18, 19, 20, and 21. Blocks 1–4 were apparently never platted, perhaps being saved for future expansion.

Full blocks measured 280.5’ (17 rods) square and were divided into eight lots bisected by two 16.5’ wide alleys running at right angles. As it turned out, only Blocks 9 and 7 were fully lotted, with Block 10 consisting only of Lots 1 and 8; Block 6 remaining totally unlotted; Block 5 containing Lots 1, 2, 3, and 4; Block 21 containing Lots 1 and 2; Block 20 containing only Lots 1, 2, 3,and 4; Block 19 containing Lots 1 and 2 (each as large as two regular lots; and Block 18 containing Lots 1, 2, and 3.

Water Street (now North Adams Street) divided Blocks 5, 6, 7, 9, and 10 from the riverfront Blocks of 18, 19, 20, and 21.

Connecting Summit Street with the Fox River were (from north to south) First Street, Second Street, and Main Street. Third Street connected Summit Street with Water Street but apparently did not go all the way through to the riverbank as did the other streets.

As platted, and just like the lots in the Village of Oswego, each standard lot was 66’ (four rods) wide by 132’ (eight rods) deep.

Exceptions were the riverfront lots, which varied considerably in depth, and Lots 1 and 8 in Block 10. Lot 1 was 132 feet deep but was only 53.5 feet wide at its west end, narrowing to just 40 feet of frontage on Summit Street. Lot 8 was 66 feet wide on Water Street, but narrowed to 55.5 feet on the alley at its east border. Exactly why this was remains one of local history’s mysteries.

Streets platted by Rising and Bell varied in width from 60 to 70 feet. As platted First, Second, and Third streets were 60 feet wide, while Main and Water streets were 70 feet in width.

Besides laying out the village of Troy, Rising and the Robinson estate also added a sawmill at the east end of their dam to compliment the gristmill at the west end of the dam. It was located on Lots 1 and 2 of Block 19 in Troy.

In 1852, Rising sold the mills, dam, store and all other parts of Troy that remained unsold to William O. Parker. Parker had been born in Canada in 1828 and moved to Illinois with his family in 1836. In 1851, Parker moved to Oswego, purchasing the Rising milling operation and the rest of Troy just a year later. And with the sale, the milling operations on both sides of the river became collectively known locally as Parker’s Mills.

Five years later, in February of 1857, an exceptionally severe spring freshet—flood—occurred and destroyed Parker’s east bank sawmill and the dam, and damaged the grist mill on the west bank. Although Parker suffered damages of $3,000, a considerable sum in 1857, especially since a devastating financial depression was about to hit, he rebuilt the sawmill and dam and repaired the gristmill and store. And his businesses continued to thrive, serving the area for decades thereafter.

Then in October 1870, the Ottawa, Oswego & Fox River Valley Railroad reached Troy and Oswego, sparking a business boom. According to contemporary maps, the railroad right-of-way passed through Troy along the north-south alley splitting Blocks 7, 9, and 10.

But the arrival of the railroad probably also spelled the eventual doom of Parker’s milling operations. With the railroad providing cheap, all-weather transportation for flour and lumber coming in and farmers’ crops and livestock going out, water-powered mills up and down the Fox River Valley began closing down.

Perhaps not realizing what was about to happen, about 1870, possibly prompted by the arrival of rail transportation to get products to market, Parker added a furniture factory to his sawmill. The factory manufactured a number of items including chairs and other furniture made from the area’s extensive supply of black walnut trees. A solid walnut washstand could be purchased, unfinished, from Parker’s factory for less than $1. An example of one such Parker washstand is on display in the gallery at the Little White School Museum in Oswego.

Another person who profited off the railroad’s arrival was my great-great-grandmother, Mary Ann Minnich. She and her husband had moved into one of the houses in Troy about 1867, and she apparently figured renting sleeping space to railroad workers would be a good money-maker as construction went through Troy and Oswego.

The workers were a fractious lot, however, as the Kendall County Record reported on July 14, 1870 while the line was still under construction: “Some excitement prevailed here last evening among the railroad laborers owing to a report that they would not get full pay for labor performed; a party started for headquarters (Ottawa) in consequence of it; [John W.] Chapman went with them; pretty much all the male population of the “Patch” [Troy] was in town.”

The next week, on July 28, the Record reported: “A number of suits for riot, assault and battery, breaking of the peace &c., has been commenced before both Justice Fowler and Burr by the belligerents of “the Patch,” [Troy] which by agreement were all merged into one and tried Wednesday and Thursday of last week. Smith was the attorney for Gaughan. Hawley and Judge Parks of Aurora for Monaughon & Co. John Monaughon and Michael Ruddy were held to bail to keep the peace and appear at the next session of the circuit court.”

The drama in Troy didn’t end there, either. Far from it, in fact. Just a few weeks later love in Troy was in the news. The Record reported on Sept. 1, 1870: “For once, there is a first class item, an elopement. One evening the latter part of last week, Pat Monaughon, a boy of 19 years of age eloped with Mrs. Dowling and her three children; Mr. Dowling, the lady’s husband, was absent from home; both parties were residents of the Patch [Troy].”

In 1847, Truman Mudget built the first brewery in Kendall County about where the railroad tracks would pass along Adams Street to the west of downtown Oswego. But, as the Rev. E.W. Hicks commented in his 1877 Kendall County history, “the soil was not congenial, and it ran only a few seasons.”

But in 1857 local beer enthusiasts decided to try again, building a native limestone brewery along Summit Street on land just north of Oswego’s village limits. This brewery was more successful, but even though the new rail line passed close by, the brewery failed. In 1877, William H. McConnell purchased the defunct brewery, remodeled it, and reopened it as the Fox River Creamery.

“Milk instead of barley, and butter instead of beer,” Hicks, a Baptist minister, wrote approvingly, adding: “And both cows and men are the gainers.”

Although the creamery, which produced cream, butter, and cheese from local farmers’ milk, was not officially part of Troy, lying in that sort of no-man’s-land between Troy and Oswego, it was close enough as made little difference.

Also drawn by the railroad, the Esch Brothers began their Troy ice harvesting and sales business in Troy. They located their huge ice houses just north of Parker’s dam on the east bank of the river, north of Second Street in Troy. The company harvested ice from the mill pond behind Parker’s dam each winter and used the sawdust from the saw mill to insulate the ice in the huge houses. As the Record reported on Nov. 18, 1874: “The ice procurable in the mill pond is to be exported hereafter; an ice house 102 by 60 feet is now being constructed near there, or on The Patch, as the place [Troy] is usually called, by Rabe & Esch, Chicago firm.”

On Nov. 28, 1878, the Record’s Oswego correspondent reported that the ice company was expanding its operations: “Troy, our suburb, has been growing much faster than Oswego the past year; ten new buildings 100×50 have been erected there by Esch Brothers, and Co.; they being ice houses; the whole number now being 14.”

Also from May of 1878 through May of 1879, McConnell, using the new railroad, was able to ship 177,000 lbs. of butter and 354,000 lbs. of cheese from the Fox River Creamery, most of it going to Chicago hotels.

In January of 1879, the Kendall County Record reported the Esch Brother were employing 75 men in the ice harvest. It was big business. In August of 1880, Esch Brothers shipped 124 rail cars of ice from the firm’s Troy siding.

1880, in fact, seems to have been the economic high point of Troy. That year, the Esch Brothers added a 35 horsepower steam engine and an endless chain (conveyor system) to move ice from the river to the houses during harvest and from the houses to the rail cars on the firm’s siding for shipment. William Parker and Sons made a number of improvements at their mills as well that year. An addition was built to the furniture factory adjacent to the saw mill and another story was added to the mill itself. And finally, the ice company built their own buildings to house both the men and the horses used in each winter’s ice harvest. As the Record’s Oswego correspondent put it on Dec. 9, 1880: “The boarding house, a two story, and the stable constructed by Esch Bros. & Rabe [in Troy] for the accommodation of the men and horses necessary for the ice harvest are completed and doubtless the operation of cutting and storing the ice will commence immediately.”

Troy’s reputation as a lively spot continued along with its economic growth. On Aug. 18, 1881, the Record reported from Oswego: “Saturday evening a dispute arose between Henry Sanders, who had been drinking, and Cash Mullenix, and it is alleged that in order to emphasize his points, the former exhibited a pistol which caused his arrest and lodgement in the town house; during the night somebody released him by breaking out a part of a window and cutting open the door of the cell. The authorities seemed to be aware that he had gone to Mrs. Minich’s [sic] house and about 10 o’clock Sunday a posse went there and upon their approach Henry left the house and ran to the river, and a few steps into it where the water was shallow but then surrendered.”

By 1883, the Oswego Ice Company, owned by the Esch Brothers, had 25 ice houses in operation, including six new houses measuring 150’x180’. During the yearly winter ice harvest, the company housed 1,000 tons of ice daily. As part of the growing number of improvements, the company was connected by telephone to the Oswego Depot of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad to coordinate dropping off and picking up cars on the firm’s rail siding.

But in 1891, a disastrous fire struck the ice company, and before the flames were extinguished, 14 giant ice houses were destroyed and their contents ruined. The fire took place in March at the conclusion of the annual ice harvest. The company never recovered, and was–literally–liquidated.

By the turn of the century, both the grist and saw mills were no longer in operation. According to some accounts, the saw mill burned prior to 1908. The grist mill was dismantled in the 1920s by local carpenter Irvin Haines, and the wood beams and stone were used to help build Turtle Rock Inn at the west end of the Oswego Bridge.

Another try at establishing an ice company was made shortly after the turn of the century. The Knickerbocker Ice Company, Inc. purchased several lots in Blocks 20, 21, and 6 in early 1909. However, as far as is known, no ice was harvested by the firm as the dam was then in extremely poor shape and the millpond badly silted up. Besides, by that time, the Fox River was badly polluted and manufactured ice was quickly replacing the old “natural” ice. No additional ice houses were built by the Knickerbocker company, and the corporation sold all its land in Troy to Central Trust of New York in 1911.

Over the years, several of Troy’s streets and alleys have been officially been vacated. All of First Street is vacated, as is the portion of Water Street (North Adams) north of Second Street. Main Street from Summit Street to North Adams was vacated, with the vacation recorded on Nov. 4, 1967, as were the alleys in blocks 7 and 9. Third Street from Summit to Water has also been vacated.

The portions of Second and Main streets from North Adams to the Fox River, however, have never been vacated, nor has the alley between lots 2 and 3 in Block 18.

The site of the Parker saw mill and furniture factory along the east bank of the Fox River in the old Village of Troy, is now named Troy Park and is owned and operated by the Oswegoland Park District. It offers picnicking and fishing from the ruins of the old sawmill mill foundation. Across the river, the site of the old grist mill is now Millstone Park, also owned and maintained by the park district.

And finally, residents living in the old Village of Troy, as well as those in nearby Cedar Glen and a few other surrounding properties, voted to annex to the Village of Oswego in the late 1980s. On Dec. 5, 1988, the Oswego Village Board voted unanimously to annex its old industrial suburb of Troy, ending a long, interesting era in local history.