As I suggested in my last post, Oswego’s downtown business district is located on Main Street, a pretty American sort of thing for a town. But there are a surprising number of towns, large and small, where the main business district is not located on Main Street—supposing they have a Main Street at all.

Take Aurora for instance, Illinois’ second city with a population of about 200,000. Downtown Aurora’s main business district—although a shadow of its former self—stretches along Broadway, not Main Street. In fact, Aurora has no Main Street any more. It used to have a Main Street many years ago, a commercial street that crossed Broadway at one of the city’s busiest intersections, but the name was changed to East Galena Boulevard a long time ago. Not so long that my mother, who was born and raised mostly in the East Side’s “Dutchtown” German ethnic neighborhood, didn’t often forget and call it Main Street fairly often before her death in the late 1980s. Today, about the only reminder the city used to have a Main Street is the old Main Street Baptist Church, located on East Galena.

Just to our north is Montgomery, tucked between Aurora and Oswego along the banks of the Fox River. Montgomery indeed has a Main Street, but it’s not really a main street, if you get my drift. Instead, Montgomery’s real main street is actually two streets, River and Webster. Montgomery, even more than Oswego, suffered from its close proximity to Aurora, which discouraged the development of a true retail business district. Instead, stores were sort of strung out along River and Webster streets—and not many of them at that. Main Street, meanwhile, runs perpendicular to Webster Street. On its south end, it’s a mostly residential street. North of Webster, Main Street is dominated by the Lyon Metal Products, Inc. factory and some other quasi-industrial properties before it reverts back to a residential area.

Plano’s Main Street, laid out from the beginning with stores facing the railroad tracks, is still its main downtown retail street.

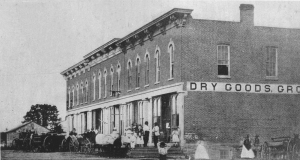

Among Kendall County’s other municipalities, Plano can be considered one with a real main Main Street, and that’s despite the city growing up as a railroad town. Classic railroad towns have their business district stores facing the tracks. Often, there are streets on either side of the tracks, each with blocks of stores facing the tracks—as long as they were designed from the ground up as railroad towns, as Plano definitely was. Lewis Steward had promised the promoters of the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad that if they extended their tracks through the extensive land he owned that he’d create a city. Which he did. Plano’s Main Street is laid out north of and parallel to the CB&Q’s main line, with blocks of storefronts laid out on the north side of the street facing the tracks so rail travelers could clearly see them.

With its stores facing the railroad tracks, Plano’s design theory was much like Oswego’s, although when Oswego was laid out by Lewis B. Judson and Levi F. Arnold in 1835, the major mode of transportation was the stagecoach. Therefore the stores were laid out facing Main Street, which was part of the western branch of the well-traveled Chicago to Ottawa Trail, running west southwest from Chicago through Naperville to Oswego and then southwest to Ottawa.

Newark, in far southwest Kendall County, was located on the same mail stage route as Oswego. As a result, Newark’s Main Street, laid out along the Chicago to Ottawa Trail, was also the heart of the village’s retail district. Like Oswego’s, Newark’s stores faced Main Street in an effort to appeal to stage travelers.

Sandwich’s main business district street is Railroad Street, with its stores and hotel facing the tracks. Meanwhile, Main Street in Sandwich runs perpendicular to the tracks and has not been an important retail area since the railroad arrived in the 1850s.

Sandwich, located just across the Kendall County border in DeKalb County, is an interesting example of a town that predated the arrival of the railroad, but which, nonetheless, ended up looking like a traditional railroad town–except for the fact that Sandwich’s Main Street runs perpendicular to the CB&Q rail line. When the rails arrived in the 1850s, the village’s fathers simply changed the emphasis of its business district from Main Street to the aptly named Railroad Street. Main Street still exists as a connector without much commercial impact.

Then there’s Yorkville, the Kendall County seat, which has two Main Streets, neither of which are mercantile hubs. Yorkville started out as two adjoining villages, Bristol and Yorkville. Each of the towns were platted with their own Main Streets, Bristol’s running east-west, and Yorkville’s running north-south, each hoping to be the center of the retail trade in their towns. Instead, however, the bulk of retail businesses quickly located along Bridge Street, which ran north-south across the Fox River bridge.

Bridge Street in Yorkville became the home of business districts on both north and south sides of the Fox River thanks to the bridge crossing the Fox River. That left Yorkville with two Main Streets, one on each side of the river, one running north-south, the other east-west.

On the south side of the river in Yorkville, Bridge Street provided access up to Courthouse Hill, where the county courthouse was built in 1864. South of the river, in Bristol, Bridge Street ran past the city square park donated by Lyman Bristol and past several businesses located there to tap the trade on its way across the river.

The two Main Streets were eventually relegated to use as residential areas. In the 1957, the two villages merged into the United City of Yorkville, and the two Main Streets remained as historical artifacts, creating the interesting, and possibly unique, situation of Yorkville residents now enjoying North, South, East, and West Main Streets.

Which really does go to show that Main Street isn’t always a main street.