On a cold February night in 1867, an overheated stove pipe in an Oswego store started a destructive fire that destroyed virtually every building on the east side of Main Street between Washington and Jefferson streets in the village’s downtown business district.

The blaze was considered one more severe blow to the community, which had sustained a severe economic disappointment three years earlier when the county seat was finally moved from Oswego to the new courthouse in Yorkville.

But although they didn’t realize it in the immediate aftermath of the fire, what Providence accomplished that night would turn out to be in the best long-term interests of the town. A century or so later, what happened that night would be termed urban renewal as modern brick commercial buildings replaced existing old timber framed store buildings, some dating nearly to Oswego’s founding in the mid-1830s.

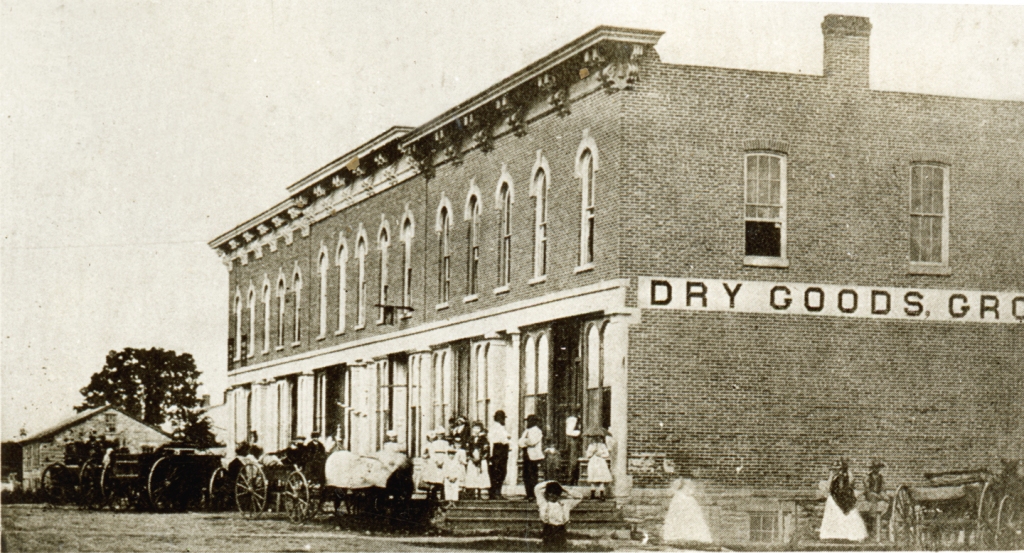

During the next year, the “Union Block” rose on the ashes of the most of the buildings that burned, although the half of the block north of the alley that bisected it that had been occupied by the stately National Hotel would remain vacant for several more years.

The evolution of commercial buildings in downtown Oswego was chronicled in a series of photographs taken over the span of several years. Those images give us a look at the broad outlines of the way commercial architecture in small Illinois towns changed with building technology over the years. Many other small towns mirrored Oswego’s experience across the nation, including most of those right here in Kendall County.

The original buildings that went up in Oswego’s downtown were virtually identical to those built during the same era up and down the Fox River Valley. Using the abundant timber growing along both sides of the river, early merchants built timber framed stores and other commercial buildings. In the 1850s, with the invention of balloon framing—similar, but not identical, to the technique used to build homes today—some of the older timber framed buildings were moved out of the downtown to be replaced by newer structures.

For instance, the village’s first store, established about 1835 by Levi F. Arnold in the middle of what is today the downtown business district, was eventually moved near a home in the village where it soldiered on as a barn for many more years.

The stores built during that era were of the old style shops with small sash windows. Window-shopping during that era was virtually unknown; customers went to shops where they knew what goods were available and bought what they needed.

But by the 1860s, a retail revolution had already taken place, led by such visionaries as Alexander Turney Stewart. Stewart built his eight-story Cast Iron Palace in New York to market a huge variety of goods to the city’s residents, rich and not rich alike. The new use of cast iron framing allowed soaring windows and airy interiors. . The size of the windows was limited in width, but not in length after a process was invented to produce what was called cylinder glass that produced long, narrow sheets of glass. The tall windows allowed much more natural light into the buildings’ interiors than the old double-hung sashes, dramatically brightening the interiors and making them much more inviting for customers.

The new buildings in downtown Oswego were designed in the then-fashionable Italianate architectural style using decorative cast iron fronts of the kind pioneered by Stewart that sported tall, narrow windows to let in light as well as to entice customers with the goods they could see from the street.

Although the east side of Main Street got its forced architectural facelift in 1867, throughout the rest of the 19th Century, the west side of Main Street was still dotted with old small-windowed frame buildings from the 1840s and 1850s. Then in the 1890s, things took a dramatic change in direction.

The first of the modern all-brick buildings on the west side of Main between Jackson and Washington Street in the heart of Oswego’s downtown, was the ornate Oswego Saloon. Begun in the autumn of 1897 on the west side lot bordering the mid-block alley to the south, it was designed by its owners to be an architectural marvel. Reported the Kendall County Record’s Oswego correspondent on Nov. 3: “The new brick building, which is to be built of the most modern style of architecture and finish, will be the pride of the town. We folks who have been in the habit of saying that “saloons are no good” will have to dry up. The building is about ready for the roof.”

It made use of improvements in commercial building technologies—including glassmaking—that had been developed during the three decades since the Union Block had been built. As the Record reported on Dec. 22: “The large plate-glass was put in place in the new saloon building and the steel ceiling overhead has been put on by John Edwards.”

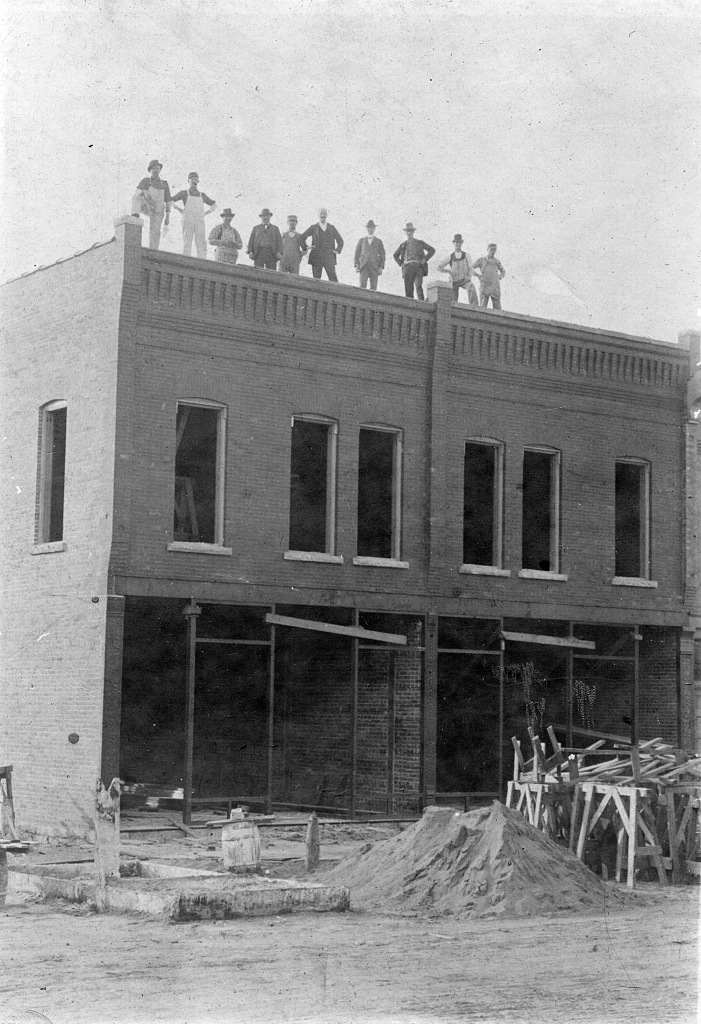

Then in 1898, Oswego businessman and livestock dealer Charles Knapp built his two storefront brick commercial building adjoining the Oswego Saloon to the south. The Record reported on April 20: “ The work on the Knapp new buildings is going forward very rapidly. The laying of the brick is expertly and expeditiously done. A few fair days would reach the putting on of the roof.” Like the Oswego Saloon, the Knapp Building was two storeys, with the second floor proposed for use either as apartments or a hotel.

By June 22, the Record’s Oswego correspondent could report: “The Knapp buildings are nearly completed and now receiving the finishing touches. The metallic ceiling of the hall and rooms connected with it are made dazzling by paint.”

The building’s first tenants were the Croushorn furniture store and funeral parlor and Knapp’s own meat market.

Then, finally, in 1899, Oswego businessman John Schickler built his new brick three storefront building at the northwest corner of Main and Washington across from the 1867 brick Union Block. Like the Oswego Saloon and the Knapp Building, Schickler’s two-storey building featured ornate cast iron fronts with much wider plate glass windows.

These new “show windows” (the term was an American invention) turned the buildings themselves into advertising media, keeping the goods—and the customers—inside on permanent display.

One-story buildings, primarily the all-brick Burkhart Block diagonally across the Main and Washington Street intersection from Schickler’s building following Schickler’s architectural lead were later built on South Main Street.

The next downtown building featuring then-new state-of-the-art commercial architecture wasn’t built until more than a half-century had passed. In 1954, Bohn’s Super Market rose at 60 Main Street on part of the east side site once occupied by the old National Hotel. A classic 1950s era commercial structure, Bohn’s had aisles wide enough to accommodate shopping carts. While self-service (“cash and carry”) was encouraged, Bohn’s still accommodated residents who called in their grocery orders and expected delivery.

Like commercial buildings in Kendall County’s other small towns, other retail innovations such as elevators were unnecessary, although downtowns in the larger nearby communities of Joliet and Aurora made full use of them and others, from chain stores to public transportation. But the economic impact of new commercial buildings making use of the technology available at the time had major impacts on the communities in which they were built, no matter how small.

Kendall County towns where growth continued in the late 1800s and early and mid 1900s all eventually sported buildings like those built in Oswego. Looking at commercial architectural styles in Yorkville, Plano, and Sandwich is a good way to tell when growth took place. Although most of the graceful old narrow-windowed cast iron front buildings have had their facades “modernized,” the discerning enthusiast can still track the evolution of commercial architecture in local towns. And as new growth begins to accelerate in the face of ever-increasing development, those remnants of the county’s commercial past provide a link with the area’s fast-disappearing history.