I admit I’m often a bit slow on uptake so I didn’t really occur to me until a couple weeks ago that this year will mark the 30th anniversary of the start of efforts to catalog and safely and properly store the mass of artifacts, photographs and negatives, and archival documents we’d collected at what had become Oswego’s Little White School Museum.

So after the thought occurred, it also occurred to me it might be valuable for others to learn the story of how today’s museum collections came to be created and managed. Before the colors fade, here’s a brief rundown of what took place all those years ago that resulted in the museum the community has today.

The project to save the historic building and create a local history museum in it had begun in 1976 when a grassroots group of local residents established the Oswegoland Heritage Association (OHA) to oversee the project and raise funds to finance it. In a way, it was sort of reminiscent of one of those old Mickey Rooney–Judy Garland movies where they say “Let’s put on a show!” to raise money for some project or another. But this project turned out to be a lot more complicated, with many more moving parts, than one of those old movies let on.

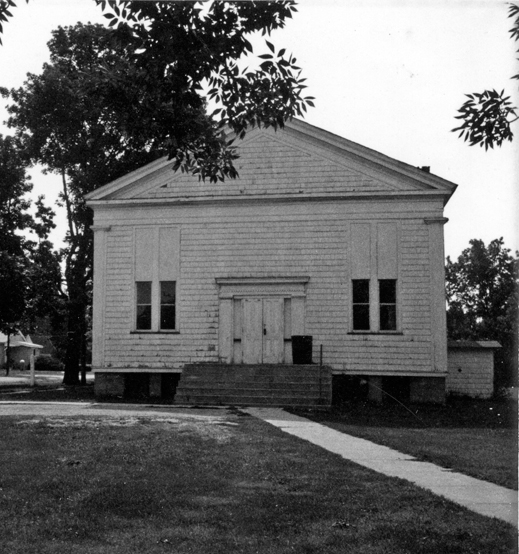

The first thing that had to be done was to stabilize the badly deteriorated building, which required deciding what kind of project we were going to do, restoration or renovation. The OHA Board decided to restore the exterior of the main structure, built in 1850, to its looks in the earliest image we had of it, which dated to 1901. At the same time, it was also decided to renovate the badly deteriorated Jackson Street entrance hall and classroom addition, which had been added in 1936, to accommodate visitors and create a community museum room.

So, right off the bat, the OHA was working on a two-track project.

Also, as soon as the community learned the building was undergoing restoration and renovation, they began dropping off Oswego-related historical artifacts, photos and negatives, and documents. With two complicated projects already underway, those items were simply warehoused in the building’s basement to await figuring out what to do with them sometime in the future.

As it turned out, the exterior restoration and the renovation of the entrance hall and the museum room were completed by Oswego’s sesquicentennial celebration in 1983, thanks to local contractor Stan Young. He’d attended the Little White School as a youngster and figured out ways to achieve everything from restoring the building’s wooden front porch to recreating its missing bell tower.

The museum room—soon to be renamed the museum gallery—was filled with Oswego history exhibits created by OHA Board members and volunteers. It opened to the public in April of 1983.

In the meantime, the OHA Board was discussing what ought to be done with the building’s main room, renovate the two existing classrooms, front entrance vestibule and basement stairways, or remove the drop ceiling and interior walls and stairwells that had been added since 1930 and return the room to its original open 36×50 foot appearance during its original use as a Methodist-Episcopal Church and, starting in 1915, as a one-room school for grades 1-3. After much discussion, the board decided on the restoration option for the main room, taking its look back to the era of transition, 1913-1915, when its use changed from church to school. My friend from high school, Glenn Young, was persuaded to oversee the project, something he’d be closely involved with for the next 19 years.

Restoration work, consisting of removing all the interior walls and the drop ceiling began in the fall of 1983. Fortunately for us, Caterpillar, Inc. was undergoing one of its periodic strikes and my high school classmate Jim Williams, and cousin-by-marriage Omer Horton were both free to volunteer partial days on the project, getting it done much faster than we’d expected. It was about that time the park district retained Oswegoan Mark Campbell and Don Drum to help with the project every Saturday.

But by the fall of 1993, a decade later, the interior restoration project was far enough along that the board decided to finally get serious about organizing, cataloging, and properly storing all those historical photos, documents, and artifacts that continued to arrive. But, again, it proved more easily said than done.

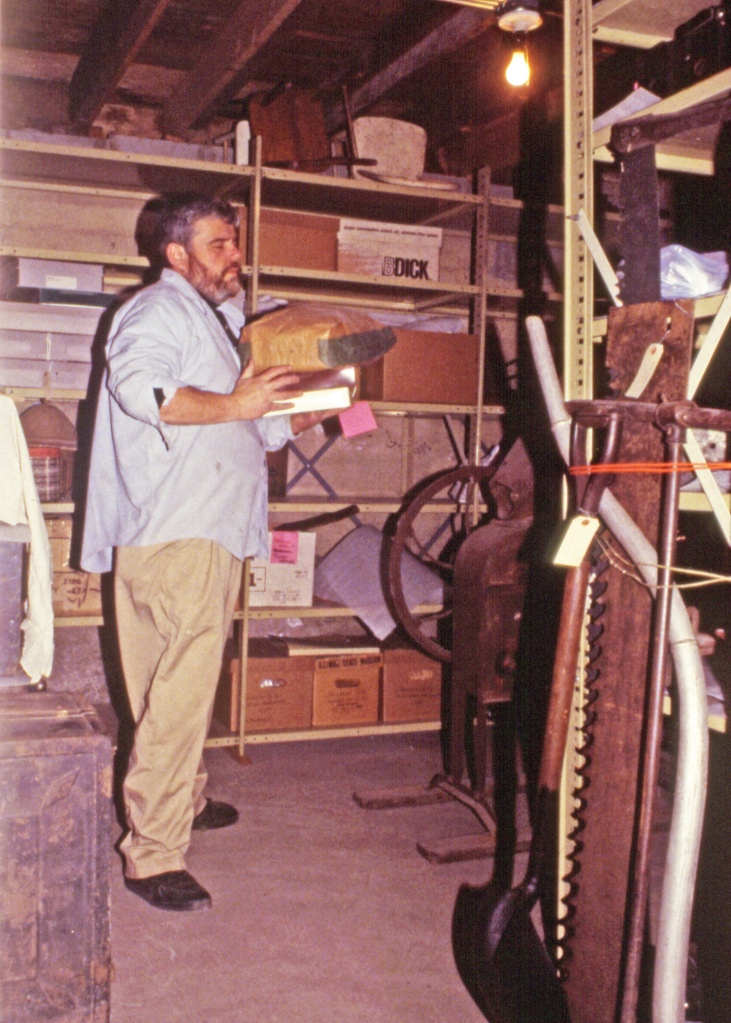

The basement storage area was an unorganized jumble of priceless items that were in danger of damage, and there was no museum office where files could be created and kept. So, the first item of business was to clean out a corner of the basement to create suitable office space. That required coordination with the restoration project as the two efforts were going on at the same time. It took a while, too, because volunteers only worked Saturday mornings and park district-financed construction people only worked Saturdays as well.

A bit earlier in time one of the old farmhouses on Douglas Road in Oswego was being demolished to make way for new development. We were given permission to salvage the kitchen cabinets and doors and doorframes from the building, which were used in the new office. Some used countertops were also located that fit the cabinets just fine. A couple used file cabinets and desks finished out the furnishings.

Also about the time we were ready to start the organizing and cataloging project, we were lucky enough to gain the services Stephanie “Stevie” Todd, of one of the best historical researchers in the Fox Valley. She was able to procure the volunteer services of Keith Coryell, an actual museum professional who was (fortunately for us) between jobs at the time and willing to help us get started with our project.

We figured early on it was vitally important to get off to a good start. We’d heard horror stories of museums where they’d had to change their systems of cataloging items for one reason or another, sometimes losing track of huge portions of their collections. Because the most important trick with museums isn’t cataloging and properly storing items, it’s the ability to find them again once they’re placed in their forever storage home.

Also, we had to decide exactly what our collection was supposed to represent. Those of us who like old things have an urge to save everything, but we knew we had limited storage space, and so had to decide what our paramaters were. The OHA Board decided the items we collected were to directly deal with the 68 square miles inside the Oswego School District, including the families, businesses, farms, towns, and other things that included.

The “what” settled, the questions related to “how” were next to solve.

We had decided years ago to use a trinomial artifact numbering system, with the first number being the year the item was donated, the second number denoting the order it was received during the year it was donated, and the third number affixed to individual items in multi-item collections.

That was fine and fit in with they way many museums numbered their items. The next decision was whether to number all classes of items—documents, photos, and artifacts—the same. At that time, many museum had different numbering schemes for each type of item, which didn’t seem sensible to us. We figured if someone was going to come to the museum looking for, say, items dealing with the Shoger or Burkhart families, they’d want to see a listing of every item, no matter what kind it was, related to the family or other topic they were searching for. We also though our system would be of benefit for our own staff when, say, looking for items to create exhibits. If we were doing an exhibit on Church School or Bohn’s Grocery Store, we’d want to turn up whatever photos, documents, and artifacts in the collection.

And to keep track of all those items we were looking at we knew from the beginning we were going to need some sort of computerized database system. We’d dabbled with creating card files of artifacts at random periods earlier on, but couldn’t really make them work.

There were commercially available museum cataloging systems available, but at that early time, many of them insisted in treating photos, artifacts, and documents differently, which we didn’t want to do. Further, there were no Macintosh-based cataloging applications available. We’d decided to use Macs because we also wanted to create our own graphics—signs, labels, document and photo scans—and newsletters, and Macs were the gold standard for doing those things.

So, we ended up creating our own cataloging database using the Mac-compatible FileMaker Pro application. We wrote to more than a dozen area museums requesting copies of their accession sheets—accessioning is the formal, legal process of taking ownership of items donated to a museum or library—so we could figure out which fields we wanted to make sure we had in our own database.

In the early spring of 1994, I’d taken a course out at Waubonsee Community College on museum planning that Keith Coryell had given. And in that course, he strongly recommended that a museum needs a director to oversee the technical aspects of cataloging and storage of donated items. I took that lesson and the data backing it up back to the board and in August 1994 they appointed me museum director with the task of coordinating and overseeing the Little White School Museum’s collections management.

Because the main volunteer emphasis was still on the main room restoration project, we solicited other volunteers to help clean up the basement area, get the floor and walls painted, and staple Tyvek fabric to the ceiling to stop 140 years worth of dust accumulated in the floorboards from sifting down into the basement and onto the artifacts and other materials being stored there. Fortunately, within a couple years, the park district agreed to finance installation of a new drop ceiling (we were able to find a bunch of used light fixtures for the project) that eliminated the sifting dust problem and brightened up the area considerably.

By the autumn of 1994, we were finally ready to begin seriously addressing the collection. Stevie, Keith, and I began showing up at the museum on Thursdays to work on the collection, beginning with a “macro sort,” which left me free to help with the main room restoration project on Saturday mornings. Keith explained the macro sort consisted, basically, of putting like items in piles—textiles, documents, 3-dimensional artifacts, and photogrsphs and negatives.

We also assembled used shelving we’d acquired in the building’s old basement coal room, which we’d painted as a spot where we could temporarily store our sorted piles.

Keith explained the need for acid-free storage media—folders, envelopes, and boxes—as well as acid-free paper with which to make photo copies and so off went our first orders to Hollinger, Inc. and Gaylord, Inc. for the necessary materials. Full-sized and half-sixed record storage boxes from Hollinger, it turned out, were the museum industry standard, and no matter from which manufacturer they were acquired, they were called Hollinger boxes. We were going to need a LOT of both sizes of Hollinger boxes.

The seemingly little things we decided then have stood us in good stead. For instance, when we were planning our needs, we decided that all our file cabinets should be legal and not letter sized. That’s because legal documents are, naturally, legal sized. Documents, Keith, explained, need to be stored flat and unfolded. And while letter sized documents fit in legal sized folders, they don’t fit in letter sized folders.

Another important decision we made was to store our photos—including postcards—in correct archivally-safe pocket pages in three-ring binders. We decided that would allow easy and safe access to the photos, which, 30 years later, it certainly has.

But what about over-sized documents and photos that wouldn’t fit, unfolded and flat, into legal file folders? For that, we needed flat files. And like the helpful Caterpillar strike back in ’83, fate stepped in once again. The venerable Equipto manufacturing company in Aurora was closing its plant, including its showroom. Mark Campbell used his connections to broker a donation from Equipto of a large set of flat files and a unit of rolling shelving that had been on display in their show room. Mark was also able to figure out how to get the storage equipment moved to Oswego and into the museum’s basement storage area. Oversized documents and photos required oversized folders for storage, and fortunately we found all kinds of those in the Gaylord, Inc. catalog.

Remember all those Hollinger boxes we had on order? We needed someplace to safely and efficiently store them, so we checked with Glenn Young. He agreed to take time out from the main room restoration project to build custom wooden shelving perfectly sized so each shelf would hold six full size Hollinger boxes. We also got the donation of some surplus bookshelves from the Oswego Public Library.

We’d decided to make the basement’s old furnace room, which had been separately walled off sometime in the 1950s, our archival storage area. Its walls were all concrete blocks and it had a fire-proof steel security door, making it the most secure room in the whole building. After we put a couple coats of acid-free paint on the wooden shelving Glenn had made, he installed them and the four steel bookshelves in the archives storage room.

So as 1994 turned into 1995 while sorting and storing the results of the macro sort continued, we were finally ready to start formally accessioning and cataloging all those items that had arrived during previous quarter century. The first really new item was added to our new database on Feb. 14, 1995 while we started work on the backlog, including Dick Young’s extensive collection of Native American stone projectile points and tools collected in the Oswego area.

If the dates donated items had arrived were still with them along with the donors’ names and (hopefully) addresses, we used those to formally accession the items. If we didn’t know when and who donated an item, it was given an “X” instead of a date leading number, denoting “Found in Collections.”

As it turned out, Dick’s collection was the first one we had complete provenance on–a fancy word meaning we definitely knew where and when it came from—and so it got the first verifiable number, 1983-1, with the first point, numbered 1983-1-1, a Snyder projectile point dated to 500 BCE.

And from there over the years, a changing, but always dedicated core of volunteers, and lately paid part-time park district staff, have kept at cataloging and adding capabilities to the collection and to the process of managing it. Keith Coryell got a permanent job, Stevie Todd moved on to other projects, and Bob Stekl and Stephanie Just came aboard for a few decades. The OHA bought a large format scanner, updated its computer equipment, bought a used large format copier, and began a collection of microfilmed documents. The park district bought a used microfilm reader/copier.

We’d bought a bale of non-archival cardboard boxes to store textiles in during the macro sort, planning to eventually transfer over to acid-free boxes. two successive matching grants from the Illinois Association of Museum’s helped fund two new shelving racks and sufficient archival quality boxes to fill them.

We kept adding shelving and storage cabinets wherever we could find a bit of space in our basement storage area, always managing to keep a bit ahead of the steady stream of new materials that always kept arriving while also slowly but surely whittling down that huge backlog that had built up. Museum Collections Assistant Noah Beckman, one of the part-time staffers provided by the park district, finally finished up the last of the initial backlog a year or so ago, completing cataloging a collection of items donated by Evelyn Heap several years before he was born! Without the OHA’s continued partnership with the Oswegoland Park District, in fact, the museum simply would not exist.

From that initial item entered into the database 29 years ago, the museum’s collection has now grown to more than 37,000 entries ranging from prehistoric stone tools made by the area’s Indigenous residents to modern high school yearbooks to photographs and documents that chronicle the Oswego community’s history from the pioneer era to the present day.

The collection continues to grow at about 1,000 items per year, each item having some direct connection to the 68 square mile area inside the bounds of the Oswego School District, saved so future generations will be able to appreciate and learn about the community’s rich history and heritage.

On Sunday, March 10, starting at noon in the museum’s restored main room, I’ll present a history of the Little White School Museum, including the building itself, the restoration project, and its current uses, and members of the heritage association board will give tours showing off some of the latest upgrades, including a new accessibility ramp and a remodeled main entrance hallway. You’re all invited. Admission is $5 for park district residents and $10 for non-residents, money that will go towards helping us protect and preserve all that irreplaceable history we’ve collected since 1976.

For more information on the museum, visit their web site at http://www.littlewhiteschoolmuseum.org.