Several years ago while doing family history research, I made connections with a distant cousin who sent me a compact disc (remember those?) with dozens of photos and documents related to my Minnich ancestors. Among the documents were letters written by my great-great-grandmother, Mary Ann Wolf “Polly” Minnich, to her daughter, who was then living out in Kansas.

The letters were remarkable for a few reasons, not the least of which was because Mary Ann was illiterate. According to the letters’ content, she dictated them to one of her grandchildren, who wrote and mailed them for her and who would then also read the replies to her. Another interesting point, for me, at least, was that at the time she was corresponding with her daughter, she was living in the ramshackle old house on North Adams Street in Oswego that was the first house my wife and I bought back in 1968.

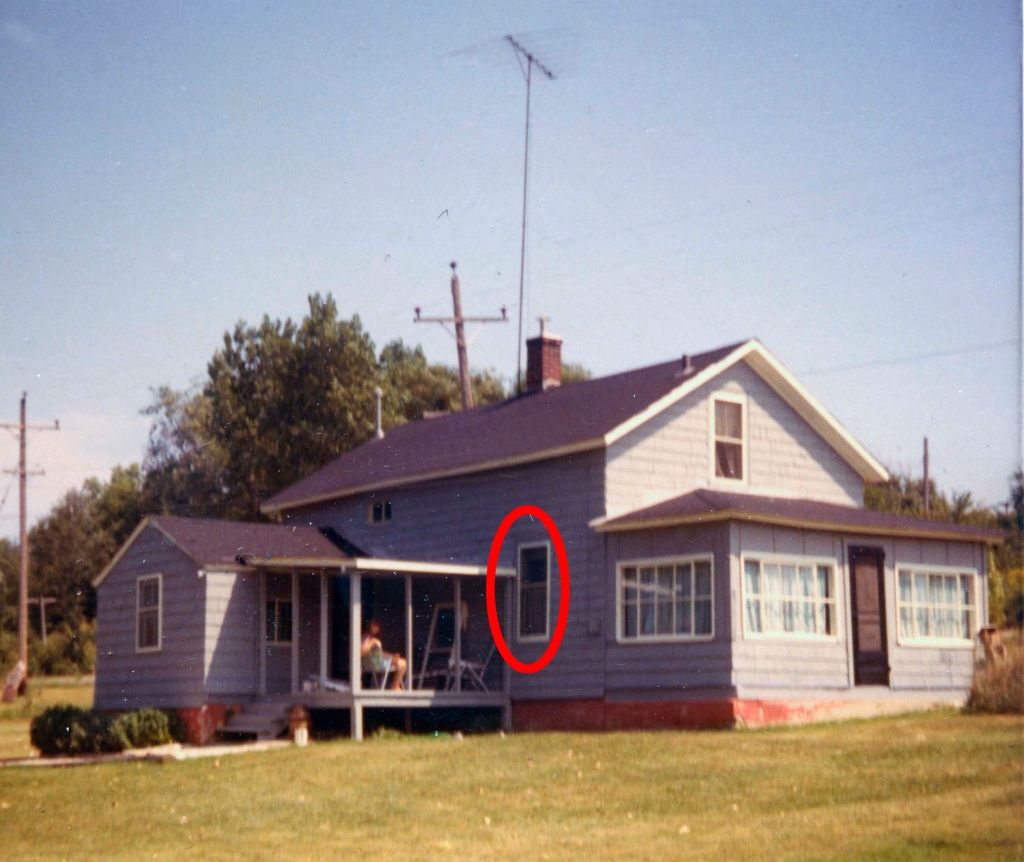

The previous owners were the first non-family members to have owned it since my great-great grandparents owned it in the 1870s. We lived there for about 10 years, and so I was familiar with its interior layout. My grandmother, who as a child had visited HER grandmother at the house told us about the interior changes that had been made, including turning my great-great grandparents’ tiny first-floor bedroom into the home’s bathroom. Which is why the bathroom had a full-sized window in it above the bathtub that looked out onto North Adams Street and the east bank of the Fox River across the road.

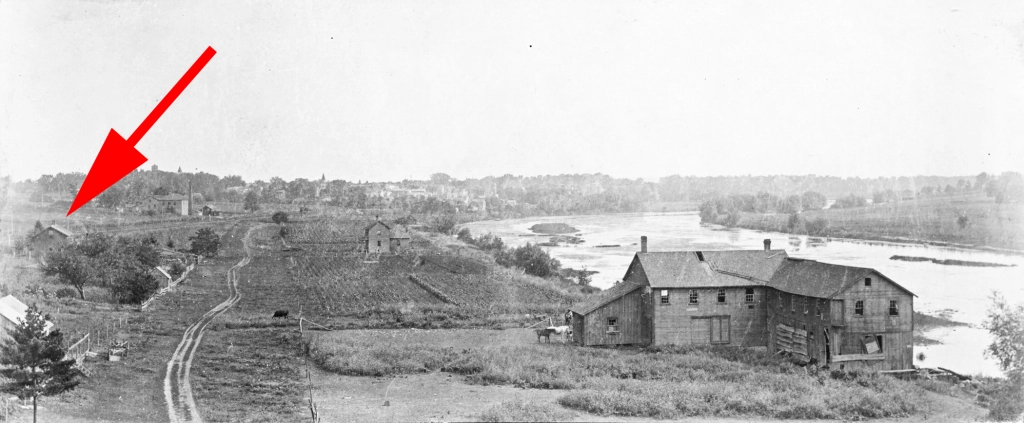

By the time we moved in back in ’68, trees lined both banks of the river, cutting off the view of Route 31 over on the river’s west side. But back when my great-great-grandparents lived there, the original old-growth trees on both banks had been cut down years before to provide everything from fence rails to firewood to building materials for homes and other buildings the pioneers needed. So someone looking out of the window in our bathroom—formerly my great-great-grandparents’ tiny bedroom—could easily have seen traffic over on Route 31, known back in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as the West River Road.

Which is a long, but I think necessary set-up for a fascinating comment I found in one of those letters long ago transcribed from my great-great-grandmother’s dictation.

By late September 1900 residents living in and around Oswego, including those living along North Adams Street, had some new sights to see and marvel at. As my great-great-grandmother put it in one of those letters to her daughter out in Kansas: “When I can’t sleep at night I can watch the Street cars run out my window over across the river.”

She could see the headlights of streetcars running on the west bank of the Fox River in 1900? Yes, as it turns out, there was, indeed, a trolley car line that ran from Aurora south roughly following the Fox River to Oswego that began service that year.

Because this kind of trolley line ran between towns and not wholly inside them, the lines were called “interurban” trolleys, and were at the height of their popularity as the 20th Century dawned.

A group of investors first proposed building an interurban trolley line from Aurora south through Montgomery and Oswego to Yorkville in 1897. The proposed line was planned to run mostly on public street and highway rights-of-way using light rails and electrically-powered trolley cars.

An early proposal to build a third-rail electric line was quickly discarded in favor of using overhead electrical lines with the cars picking up the power using car-top trolleys. Cars running on third-rail lines picked up their electrical power from an exposed electrified third rail, something that would obviously be dangerous on a rail line running through towns and the countryside and not in an underground tunnel or on an elevated track safely out of reach of pedestrians, horse-drawn vehicles, and livestock.

In August 1897 representatives of the new Aurora, Yorkville & Morris Electric Railroad company (the line’s name would change several times during the next few years) met with the Kendall County Board to start hammering out a trolley franchise agreement. As proposed, the line would begin in downtown Aurora, then run south on River Street through Montgomery, paralleling the Fox River past the new Riverview amusement park (which was to have its own station) then under construction just south of Montgomery before gently curving west to join the West River Road—now, as noted above, Ill. Route 31—for the run to the Oswego Bridge across the Fox River. There, the line would turn east, cross the river on Washington Street to Oswego’s Main Street, where it would turn south once more, following Main Street and heading towards Yorkville along what is now Ill. Route 71. Near Yorkville, the line would turn once again to follow the tracks of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy’s Fox River Branch Line between the tracks and today’s Van Emmon Road right into downtown Yorkville, where the tracks dead-ended at Van Emmon and Bridge streets.

Among the issues that had to be hammered out was who would pay for improvements the line required, such as either strengthening or rebuilding the Oswego Bridge to carry the heavy trolley cars across the river. In addition, the company pledged “that in every way possible the company would guard against frightening horses” or otherwise interfering with traffic on the roads alongside and on which the trolleys would run. In the end, the trolley company agreed to pay $3,500 towards the cost of a new, stronger box truss iron bridge to replace the existing 1867 tied arch structure at Oswego. The other issues were ironed out as well, including how the trolley line would get across the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy’s Fox River Branch rail line in Oswego.

Residents of the towns the trolley would serve were, in general, enthusiastic about the new, all-weather transportation option. As Kendall County Record Publisher John R. Marshall noted in a Dec. 13, 1899 commentary: “With only four reliable trains a day, it was hard for one to come here and be so late getting into Chicago as is necessary with the regular passenger train. With the electric accommodations, one can go to Aurora and take an early morning train to Chicago.”

Construction began in the spring of 1900 and by June 27, the tracks were completed from Aurora to the west end of the Oswego Bridge.

“Operation of the electric road from the bridge will be commenced this Tuesday afternoon by a free ride of the town and village officials to Aurora and back,” the Record’s Oswego correspondent wrote in that week’s paper. “Yorkville will have to wait about three months longer before enjoying such privilege.”

Regular service began in early July from Aurora to the terminus at Oswego, and use proved enthusiastic—and frequent. As Marshall wrote on Aug. 1: “That the Aurora and Yorkville electric road will be a great convenience and daily comfort is shown by the way it is used now between Oswego and Aurora. Every day parties drive up from about here [Yorkville] to Oswego and take the car there for Aurora, saving 12 miles’ [round trip] drive.”

Work continued feverishly the rest of the summer and into the fall of 1900 on Oswego Township’s new Oswego Bridge. Construction was also ongoing on an impressive 300-foot trestle at the east end of the bridge designed to carry the electric line up Washington Street over the CB&Q tracks to the Main Street intersection.

By late December, the new bridge and trestle, along with the tracks into Yorkville were finished and regular trolley service had begun, linking downtown Aurora through Montgomery and Oswego with downtown Yorkville. The first car arrived at the Kendall County seat at 10:45 a.m. Saturday, Dec. 22, 1900.

“There were two cars down—one with the Aurora guests, the other empty to return with a number of the distinguished populace of Kendall’s capital,” the Record reported on Dec. 26. Welcoming the new arrivals was Record publisher Marshall, who had also welcomed the first railroad train on the Fox River Branch into Yorkville 30 years before.

The interurban, providing hourly round trip service from Yorkville to Aurora from 7 a.m. until 11 p.m. at affordable rates, was part of a vast interurban network that, it was said, allowed passengers to travel via trolley from the Mississippi River, with transfers, all the way to New York City.

In an era of terrible roads, the interurban was a godsend, carrying passengers and perishable freight, including farmers’ milk, to and from Aurora. Everything from fresh bakery bread to college and high school students to office workers to shoppers rode the trolley to and from Aurora daily. For instance, war hero, musician, and star athlete Slade Cutter rode the interurban to Aurora to attend East High School. The line ran right past the family farmhouse (which still stands at the corner of Ill. Route 17 and Orchard Road) during a time Oswego High School only offered a two-year program.

But a little more than a decade after the line opened, it and others throughout the nation were under financial assault from the burgeoning number of automobiles and trucks—and government support for them.

It wasn’t so much the improved vehicles that doomed the trolleys, but the rapidly improving roads they traveled on—and their funding. From the time Illinois was settled until 1913, road maintenance was the responsibility of township property owners. Each voter—meaning men during that era—was required to work on road maintenance or to pay money in lieu of work. But with the advent of affordable, dependable motor cars and trucks, the old system was proving unequal to the task of road maintenance and construction. So in 1913, the Illinois General Assembly passed the Tice Act, removing the work requirement and replacing it with a property tax levy to fund road construction and maintenance.

At the same time, the public was also insisting on more and better roads, and in what proved a momentous policy decision, U.S. politicians decided that tax dollars should only fund construction and maintenance of roads and not the rails used by railroads and trolley companies. Although few realized it at the time, the policy meant the substantial government subsidy favoring road transport would gradually result in curtailing all of the nation’s rail systems.

And with that profound change in motion, in 1918, in spite of the nation’s involvement in World War I, Illinois voters approved a $60 million bond issue to build a system of all-weather paved roads to connect with every county in the state, the bonded indebtedness to be paid through gasoline taxes. The measure passed overwhelmingly. Here in Kendall County, the vote was 1,532-90.

The interurbans were simply unable to compete with the combination of increasingly inexpensive, efficient, and dependable motor vehicles and publicly financed roads. Starting in the 1920s, one by one, the interurban lines closed down, went bankrupt, or both.

On Aug. 6, 1924, the Record reported that “Through an order from the Illinois Commerce Commission, the interurban line from the [Fox River] park south of Montgomery to Yorkville will be discontinued.” In the event, the line carried on until Feb. 1, 1925, finally succumbing to the advance of transportation technology and the national consensus to subsidize roads but not rails.

Today, there are scant reminders of the trolley era, but look closely between the road and the railroad tracks the next time you drive Van Emmon Road into Yorkville—especially this time of year with trees and shrubs leafless—and you will see some of the last evidence of the old trolley line that was once such an important part of the area’s transportation system.

Another fantastic piece of history written here. This all makes sense now after reading this I’ve taken notice of the landmarks you wrote about and always wanted to know what and if a real system ran through these areas. The Fox Valley was ahead of its time in so many ways it seems.

Thanks for the kind words!