It’s interesting driving down Ill. Route 71 these days, watching the (admittedly slow) progress on the highway widening project between Orchard Road and Ill. Route 126. With crews having cleared the right-of-way for the project and utility crews having now moved the service lines back out of the way, the view has been cleared to get a good look at the topography in that area.

And that includes the Morgan Creek bridge. The newly cleared area offers a rare look at the usually hidden creek itself. Named after Ebenezer Morgan, one of the county’s earliest settlers, the small, sluggish creek originally drained an extensive wetland that divided Specie Grove from AuSable Grove. The remnant of an Ice Age lake, it was called by the area’s early settlers the Big Slough and had been a wildlife haven for thousands of years. In fact, when the Big Slough was being drained by dredging and channelizing Morgan Creek back in 1908, crews dug up an ancient Mastodon skeleton. And after the old slough had dried out, it proved a prime area to find the stone projectile points crafted by the region’s Native People lost while hunting.

Morgan and his friend and neighbor Earl Adams had come west to Illinois in 1831 from Chautauqua County, New York looking for likely land to settle on. The two were of an age, Adams born in August 1799 and Morgan in February 1800, and both had the initial cash to pay for their well-planned prospecting trip west.

They traveled southwesterly from Chautauqua County to Pittsburgh on the Ohio River. Then it was down the Ohio (probably by steamboat) to the Mississippi and then upstream around the southern tip of Illinois to St. Louis. There they bought horses, got themselves ferried over to the Mississippi’s east bank and rode upstream to the mouth of the Illinois River, which they followed all the way to Ottawa and the mouth of the Fox River. From there, their prospecting route took them up the Fox River Valley as they surveyed the rich land in the river’s valley.

Adams staked a claim—by treaty with the local Native People the land was unavailable for purchase—on a hill overlooking the river, a hill that in the fullness of time became Yorkville’s Courthouse Hill where Kendall County’s beautifully restored Historic Courthouse is located these days. Morgan, on the other hand, continued up the river’s east bank a couple miles farther to the mouth of a small creek, which he followed upstream eventually coming to Specie Grove, the Big Slough, and the rich prairie adjoining them. There, he staked his own claim of around 1,000 acres.

Having found what they hoped would be their new homes, the pair turned their horses northeast to Chicago, where they sold the horses, and headed back to Chautauqua County via the Great Lakes route, fully intending to bring their families out the next year.

But that was not to be. In the spring of 1832, the Sauk warrior Black Sparrow Hawk and the band of Sauk, Fox, and other tribespeople who followed him, numbering some 1,500 people, crossed the Mississippi River into northern Illinois with the intention of living with friendly Ho-Chunk people. The action panicked Illinois’ White settlers, politicians, and military officials and led to the brief, tragic Black Hawk War.

The news of war undoubtedly persuaded Morgan and Adams to wait to move west until things settled down. And by the next year, not only were hostilities ended, but the year dawned favorably for westbound settlers. Forever after called the Year of the Early Spring, 1833 started out dry and clear, with the primitive roads of the era—mostly nothing more than dirt traces across the prairie—drying out and grass greening up earlier than most could remember.

Morgan and two of his sons and the Adams family traveled overland by wagon, with Morgan driving a team of horses pulling the wagon with Adams’ wife and children and his own two sons in it and Adams driving a more powerful but slower yoke of oxen pulling the heavily-laden wagon hauling the family’s tools and other possessions. They skirted Lakes Ontario and Erie to the south and then took the old Territorial Road west from Detroit to Chicago. From there, the party headed west across the prairie to the Fox River. They stayed a day with William and Rebecca Wilson, the first settlers at Oswego, before heading downstream, Morgan and his sons to his huge claim and Adams and his family to the hill on the other side of the river.

Morgan and his sons got to work right away building a snug cabin for the family and getting things ready so that Morgan could go back to New York in the spring to bring the rest of his family west.

Just a couple years later, Adams moved his family to a claim in the AuSable Grove near Morgan before finally moving down to Big Grove Township where he lived and farmed the rest of his life.

Morgan was primarily a farmer, but he also had good business instincts. Noting that lumber was a scarce commodity out on the Illinois prairie, he and his sons dammed up the creek that was quickly named after him and built a sawmill. With Specie and AuSable groves right at the mill’s doorstep, there were plenty of of raw materials close at hand. The mill operated until the U.S. Army’s canal through the sandbar at the mouth of the Chicago River opened the port of Chicago to cheap lumber from Wisconsin and Michigan a year later.

Morgan was apparently not only well off but was also well thought of by his neighbors and interested in making his community a better place to live. He was named to Kane County’s first Board of County Commissioners when the Illinois General Assembly created the county in 1836 before Oswego Township was split off to create Kendall County in 1841. Then when the Illinois General Assembly voted to allow the formation of township governments in 1850, he also served on the first Kendall County Board of Supervisors.

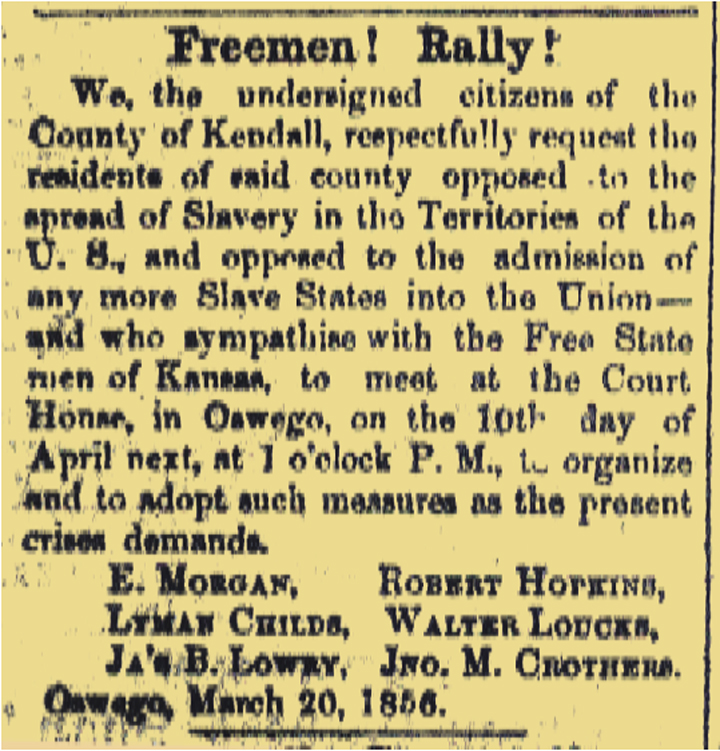

Morgan remained active in local politics his entire life, and was an active member of the Kendall County Anti-Slavery Society.

Ebenezer Morgan died on March 9, 1873, and was buried in Cowdrey Cemetery not far from his namesake creek. His wife, Lydia Ashley Morgan, followed him in death 10 years later. His friend and exploring partner, Earl Adams, had fairly closely followed him in death in 1875. With their deaths, a bit of Kendall County’s pioneer settlement era was lost. But Morgan’s namesake creek remains a tangible, living reminder of that era when adventurous pioneer families came west to the Illinois frontier to create their new lives.