A favorite mind game played by a lot of historians is wondering how things might have been, if only…

For instance, what would have happened had Lee won at Gettysburg? How would North America have fared had George Washington been killed during Braddock’s Defeat in the French and Indian War? What if the Nazis had been first to invent the atom bomb? How would Abraham Lincoln’s life been changed had his mother not died of the “milk sick” when he was a child?

Those kinds of historical speculations are in the cosmic realm—things that might or might not have changed our whole world. But there are thousands of historical micro-events at the local level that have had huge impacts on the ways in which the Fox River Valley grew and developed. Many of those incidents seem minor, but had they turned out differently, our communities would have been profoundly changed.

In the first half of the 19th Century, Montgomery was on the move as the U.S. Government’s official 1842 survey map of Aurora Township illustrates. The road from Naper’s Settlement is shown as a dotted line heading west by southwest, crossing the Fox River on “Gray’s Bridge” marked with the red arrow. (Illinois State Archives Federal Township Plats of Illinois collection)

For instance, what if Daniel Gray, the energetic founder of Montgomery, had not succumbed to illness and died during the winter of 1854? Gray was the founder and the soul of Montgomery. He was reportedly an indomitable force for development and business activities. Upon his death, Montgomery failed to live up to the potential Gray had mapped for it. Had Gray lived, the town could well have grown to rival its neighbor to the north, Aurora, in terms of its industrial base. Gray had, at the time of his death, a number of manufacturing operations going on, including a foundry and a large factory manufacturing farm equipment. At the time of his death he was working on a steam engine factory, something that would have added greatly to the village’s industrial base, not to mention that of the entire Fox Valley.

An even bigger question is what might have happened had the CB&Q Railroad crossed the river at Oswego instead of Aurora when it was extending its tracks west of Chicago in the 1850s?

That the railroad favored the crossing at Oswego was mentioned in several early histories and in at least one newspaper account from the 1850s. Whether the railroad was serious about the whole thing was somewhat questionable—after the fact stories like that are a dime a historical dozen. At least they were until I ran across a map in the Library of Congress’s collections. The map, published in 1854— “Rail road and county map of Illinois showing its internal improvements”—was designed to show the existing and proposed public improvements, including roads, canals, and railroads, in the state. The map illustrates a number of rail lines radiating west from Chicago, including the main line from Chicago to Galena, which included the Aurora Branch line.

Today, that line crosses the river at Aurora before trending generally west southwest through Kendall County on its way to the Mississippi River.

The blue line on the Rail Road and County Map of Illinois Showing Its Internal Improvements, 1854 by Ensign, Bridgeman & Fanning, New York marks the proposed route of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad as it was supposed to cross the Fox River at Oswego. After Oswego turned the railroad’s backers down, the line crossed at Aurora instead. (Library of Congress American Memories Collection)

But that’s not what the plans were in 1853 when the information for the map was gathered. Instead, the railroad wanted to cross at Oswego, and that’s exactly what the map shows. The map shows Aurora Branch line extending west from Turner’s Junction, now West Chicago, southwesterly to Batavia before heading south to Aurora. From Aurora, the line continues south along the Fox River to Oswego, where it is shown crossing the river where it is at its narrowest point, before heading southwesterly once again.

According to a newspaper account from an 1857 edition of the Kendall County Courier published in Oswego, the village fathers were enamored with plank roads, not railroads. In fact, the Chicago, Naperville and Oswego Plank Road company was busy extending a plank road west from Chicago on what would one day become Ogden Avenue—U.S. Route 34. Oswego was to be the terminus of the new road, something that would have greatly enhanced its economic standing. In addition, the Oswego and Indiana Plank Road Company was busy selling shares in their road, which was to connect Oswego with an undesignated place in Indiana. So with the chance to become a plank road hub, Oswego apparently told the railroad company to take a flying leap, which they did, deciding to cross the Fox River at Aurora instead of Oswego. And as a result of that decision, Aurora got the CB&Q shops, the roundhouse, and all the other accouterments of railroading that turned it into one of Illinois’ largest cities.

A sketch of the Oswego & Indiana Plank Road toll gate that was located about a mile and a half southeast of Plainfield on what is today U.S. Route 30 at Lily Cache Creek in Plainfield. Despite its grand name, the plank road reached neither Oswego nor Indiana. (Illinois Digital Archives and Plainfield Historical Society collections)

Oswego, meanwhile, lost out all the way around. The Chicago, Naperville & Oswego Plank Road Company went broke after extending the route to Naperville; the section to Oswego was never built. In addition, the only stretch of the Oswego & Indiana Plank Road built connected Joliet with Plainfield on the modern route of U.S. Route 30, plus an extremely short stretch west from Plainfield. It never reached Oswego, either.

It turned out that plank roads were expensive to maintain, and the tolls never covered the construction expenses, much less necessary maintenance. And they were being built just as timber was becoming scarce in northern Illinois thanks to the building boom the area was experiencing.

But the railroad did prove successful. Crossing as it did at Aurora, the line passed two miles west of Oswego, and about that far from Bristol—then the north side of Yorkville. Both towns established stations on the main line, but not until 1870 did the two towns get their own rail line, and then it was a branch line and not a main line.

What would have happened to Kendall County had Oswego accepted the rail crossing in 1853? The county seat might well have stayed in Oswego instead of being moved to Yorkville in 1864, and economic growth would likely have been significant for the whole county.

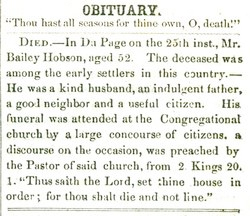

It’s an entertaining game, historical speculation is. What would have happened had the government followed through with their 1867 survey of the Fox River and made the river navigable from Ottawa to Oswego? What if a con man hadn’t sapped the economic strength of the Illinois and Midland Railroad from Newark to Millington? It’s a great game; anyone can play, and it’s free!